M*A*S*H, for three seasons you were maybe the best thing on TV, ever. You ran for a zillion more, but hey, those three are benchmarks of what TV prime time comedy could be.

We never saw him leave, but at the dawn of season four, the mighty Trapper was gone. And so too the madcap anarchy, sex and booze hijinks. This was the second MASH of the three different MASHes of my clever title (the first being the film). Thee third MASH, the longest one, had begun --changed no doubt by church group complaints initiating something called 'the family hour' meaning no risque stuff before 10 PM (which was my strictly enforced bedtime). There would be no quick sudden goodbyes now, no throng of people coming and going--doctors, nurses, orderlies--now they'd never miss a chance for Emmy-bidding sentiment, and the whole camp quickly boiled down to around eight people. I gave one of Hawkeye's steady nurse girlfriends the top photo because the way the nurses, once an array of steady girlfriends and solid supporters, all slipped away, and in came a liberal PC wholesomeness heralded by the arrival of family man B.J. Hunnicutt, and shortly thereafter, crotchety lovable family man Col. Henry Potter (Harry Morgan). Alda became just another eccentric nutball rather than a luminous star... less a playa than a perv, more likely to spy on girls in the shower then sleep with them.

I never noticed the difference in the reruns as a kid. I was too young to get all the sex references or to yet know the joy of booze. Coming back to the show now, via Netflix, I realize Alda-- who had stretched out and owned the entire first three seasons--and Wayne Rogers shared a superb crackerjack timing. Deadpan, assertive, quick-witted and very mischievous, they're so good, so on and create such a special comedic space that it takes awhile to even notice it's gone- with the 'family hour' conversion which if you're part of the generation of the era, you didn't notice because it all happened kind of currently with a national mood more like a slow slide from Weimar decadence all families united in drunk blockparty merriment to nuclear family survivalist slasher film paranoia.

But in revisiting the entire 255 episodes within a short three month period recently, I realize just how much I owe to it as far as my own style and persona, too - and how intertwined my own psyche, the natuonal pop culture landscape, and MASH itself are tied. I learned deadpan absurdity from Hawkeye: my association of true patriotism with the compulsion to continually subvert punctilious bureaucracy, my comedic timing (if any), and my love of the Marx Brothers (when I finally found them on local TV, their style seemed so familiar). With brilliant writing and one-liners bouncing off their foil, Frank Burns (Larry Linville), a wormy effeminate spoiled brat burlesque of military gung ho MacArthur-ism, I learned all the bad behaviors to avoid and how to blow them up in others. I'm still paying the price for thinking I can get away with that.

But there was also the movie... hmmm.

PS - Please forgive the length of my forthcoming post-season 3 MASH description. I kept it so, as I might mirror that of the show itself.

M*A*S*H #1 (1970 film)

I know this is an unforgivable cineaste sacrilege, but the first three seasons of M*A*S*H are funnier and overall cleverer--and much subtler--than Altman's original movie. Elliot Gould is a better Trapper in some ways but Sutherland has a lot of annoying little whistles and clicks and his vibe is far less exuberant and playful than Alda's. Sutherland's a great actor but he's never had leading man charisma. He's more skeezy, smarmy, and gauche, as evidenced in the bad taste left in our mouths from his puerile radio announcer PA broadcasting Burn's tryst with Hot Lips (all because of what? Burns made Bud Cort cry? Who hasn't!) and his pimping out of a nurse to help Painless, the suicidal dentist. These would be considered some truly creepy dick misogynist moves in today's PC climate. It might be more realistic to that most sexually free of eras than the TV series, but Altman encourages us to see these doctors' self-righteous medical muscle allows for privileged skylarking, how they're trading on their surgical skills as if some rich daddy's influence and money to get them out of any scrape with the law. Their odious frat boy dick moves are 'fun' in a depraved sort of underhanded altruism way but the only character who really deserved the shitty pranks was Frank and he's dispatched early. Otherwise the targets pretty broad. Hotlips is shamed in a shower expose for what, being haughty? Take her down a peg for being proud of her military career rather than just being a lapdog to Tom Skeirtt?And how is Burns worse than the others? Ho-John, the Korean kid, for example, gets taught English via the bible by Duvall's Burns --but that's bad, as Christians are buzzkills --but if Ho-John serves the 'cool' surgeons drinks and cleans the tent for pennies, that's good? Even an old reprobate like me has the urge to throw a yellow flag down over that kind of double standard snottiness. Don't read books, Ho-John, you not velly smart- you Ko-rean fellow, make good drink for white man!

Altman's film does rule the TV series in two areas: 1) sound design: overlapping dialogue and noisy outdoor recording making it feel much more vivid as far as an actual field hospital. And 2) it has the most OR blood, a lot of it. They'll talk about the blood in the TV show, and occasionally they'll get some arterial spray, but it's nothing like the film. These people are awash in blood, and the human body's interior is revealed in all its hideous glory.

|

| Put your tongue in your mouth, "Hawkeye" |

But on the plus: the evolution of a few side characters depicted in a cool background scenes: Bud Cort goes from wild-eyed quick-to-cry innocent intern, accused of killing a patient by Frank Burns and 'dumb enough to believe him' -to ending as a smooth lover boy, all while never leaving the periphery of the frame; Major "Hotlips" O'Houlihan (Sally Kellerman) goes from uptight military ritual loving stick-in-the-mud, to a chill girlfriend of Duke Forrest (Tom Skerritt), one of the cooler doctors (his character doesn't last into the TV series - just as the "O" is dropped from Margaret's last name). The moral is: as soon as you learn to laugh when you're pranked, instead of fuming in indignant outrage and running to the colonel, then you are no longer an outsider. That's not really a moral though, just dehumanizing. Rapists think the same thing sometimes. Welcome to the fraternity, Sheryl!

M*A*S*H #2: TV Series (1972-1974)

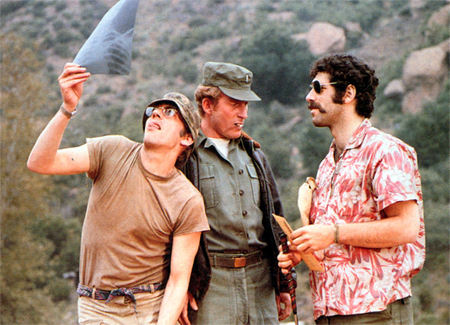

Skirting the rim between offensive sexism and good-natured tomfoolery, robust antiwar pacifism and broad compassion, the first three seasons of the TV show--guided by the exquisite judgment of Larry Gelbart--showed Americans of all ages the core of sanity within madness, the ultimate Bugs Bunny in Bosch Hell trip. Alan Alda as Hawkeye Pierce was the combination Groucho Marx and Dr. Kildare we'd been waiting for. He had such impeccable comedic rapport with his buddy Trapper (Wayne Rogers) it was as if Howard Hawks was directing at the peak of his His Girl Friday rat-at-tat-tat overlapping conspiratorial dialogue-- episode after episode. Seldom without a broad on their laps, a golf bag slung on their backs, a drink in hand at all times (or scalpel), the pair still haven't been equaled in consistent highwater brilliance. And Col. Blake wasn't too far off that mark, either, relying on Radar O'Reilly (Gary Burghoff - the only actor carried over from the film) to handle the baffling minutiae of army life, while he dithered quietly in the nurse's tent or fiddled with fishing lures. Hawkeye was single but Blake, Trapper, and wormy, effeminate but super gung ho Frank Burns (Larry Linville), were all married with kids at home. Their fooling around with the nurses on the side is just how it is, there's never any real remorse, or even condemnation from the show's subtext...At least not in these first three seasons, not in this "second" of the three distinct MASH incarnations.

A classic example of the great dichotomy between these first three seasons and the latter million can be found in the episode where the boys smear chloroform on Trapper's boxing gloves to win a match against a rival camp's champ. This kind of underhanded behavior is hardly exemplary--even if the match is grossly unfair (the other guy's a heavyweight, Trapper's a middleweight at best--but the writer clearly didn't know about these things) and yet we're expected to boo Burns and Houlihan when they sneak in a bottle of regular water in place of the chloroform, which is actually the honest thing to do. Geniously subversive, but without needing to make it a big satire on American jingoism set to Sousa ala Altman. In later seasons if anyone did such a thing it would result in a huge crisis of conscience, a public shaming, a patient homilie from Colonel Potter, and so forth.

A classic example of the great dichotomy between these first three seasons and the latter million can be found in the episode where the boys smear chloroform on Trapper's boxing gloves to win a match against a rival camp's champ. This kind of underhanded behavior is hardly exemplary--even if the match is grossly unfair (the other guy's a heavyweight, Trapper's a middleweight at best--but the writer clearly didn't know about these things) and yet we're expected to boo Burns and Houlihan when they sneak in a bottle of regular water in place of the chloroform, which is actually the honest thing to do. Geniously subversive, but without needing to make it a big satire on American jingoism set to Sousa ala Altman. In later seasons if anyone did such a thing it would result in a huge crisis of conscience, a public shaming, a patient homilie from Colonel Potter, and so forth.Best of all, in this second MASH nurses were allowed more than a single episode for their romances. Time and again a spark would form, and the nurse would linger awhile, only to be shipped out by vindictive Margaret, as they were rotated along (perhaps to stop them from getting pregnant?) If not, Hawkeye sometimes had to break it off with them if they wanted to get married, and so forth. This was always neither a condemnation of either side, no one was 'slut-shamed' ever on the show, it was just mined for comedy and truth rather than what would come after season three, sentiment and pathos.

But season three ended. The easygoing Colonel Blake was rotated home, and his helicopter was shot down--it was a spur of the moment thing at the very end of the final episode. Added in the very last scene of the last episode of the series, it proved an eerie omen. More than just a season ender, it was a rip in the time continuum, a harsh reminder of 'what really counts' in ways for example, that new Amy Schumer movie, Trainwreck (2015) turns out be. I guess in MASH it works in the context, for as I well know, the sudden death of a loved one sends even the staunchest swingers rushing home to their families, seeking some footing on what was suddenly a very unstable fun house floor. As we learned when season four commenced, nothing would be the same again.

The eighties would not hear of it.

M*A*S*H #3 (1974-1983)

Thanks largely to the frank examinations of prevailing racist, sexist, homophobic dogma of middle America and the working class via the continual battle between the liberal Meathead and Sally Struthers vs. the implacable Archie Bunker in the show in the slot right before M*A*S*H, All in the Family, the major networks bowed to morality group pressure to institute 'the Family Hour' in 1974, which enforced a more gentle, morally conservative approach to content, at least until 10PM (M*A*S*H came on at 8:30). The unheralded (contract negotiation-based) departure of Hawkeye's partner in womanizing, Trapper John (he left sans tearful goodbye as he expected to return next season); Blake's death and tearful exit, and (behind the scenes) co-creator Larry Gelbart's, all heralded the arrival of the Family Hour in a shower of blood. The loss of two of the show's extramaritally libidinal characters led to a drastic drop in premarital sex on the show, for now Hawkeye had no wingman for comparing score cards with, so that whole aspect--so prominent in the first three seasons--was replaced by sentimental blarney worthy of John Ford: sing-a-longs, prayer and dewey gazes. The bland 'sensitive' doctor and devoted Mill Valley, CA family man BJ Hunnicutt replaced Trapper. The wizened paternal Col. Potter came in as the new CO, and the show quickly became like a freshly neutered dog.

I liked BJ more than Trapper as a kid; I found him less threatening, more like a fun male babysitter rather than an older brother's cool van-driving friend who lets you sip from his beer at the ball game. But now, after my own decadent arc has dragged me into an older demographic, BJ seems hopelessly square, full of tired pranks that prefigure the sanitized monkeyshines of Jim in The Office, with a family that he stays loyal to back home, giving him a firm moral high ground, so when Hawkeye sleeps with a currently married ex-flame, well, BJ is not one to tell other people what's right and wrong (he says), but he sure will lay a sad-eyed guilt trip from ninety paces. Pictures of BJ's baby daughter and letters from Peg his wife (and Potter's wife Mildred - we come to know their names painfully well) are invoked so often they become characters without us ever seeing them. Obvious episodic messages like "war is hell" and "Koreans are people too" take center stage over psychoanalytical anarchy. Hawkeye's still a prankster: "hardly military issue but he's a damn good surgeon" notes Potter. But he becomes also an emotionally sophisticated sage to the naif Radar: "people die, Radar. Even bunnies or little wide-eyed cherub soldiers." So you know, now he has to live up to Radar's corn-fed ideals.

I like Col Potter much better than BJ this time around the run. He's at least a well-rounded character, better able to reign in the military bureaucratic fetishizing of Hot Lips and Burns than Blake could, but BJ Hunnicutt is a dire signifier who makes us realize just how sublime was the comic timing between Trapper and Hawkeye and their interaction with a roster of rotating nurses, including an adorable doe-eyed nurse (top) Marcia Strassman. She was fought for in an early episode, and then forgotten. We still miss her.

Good writers know that the more specific you are the more universal - but the reverse is also true - when the show veers away from the web of supporting characters all working more or less in service of the Army, it stalls out. We get a lot of moral dilemmas solved with generic pop psychology, and the bulk of the actual comedy coming from Klinger's parade of frocks and escape attempts. One is apt to give up and move on but as kids I well remember we loved Col. Potter and found B.J. Hunnicutt a reassuring presence and thought the earlier seasons too unnerving - when Trapper was around the adult themes soared over our heads (I was nine-ish); and the pair seemed very insular, like Trapper was the dad's drunk friend who crashes father-son bonding time in Let the Right One In. But now that I'm far older, it's of course the reverse, especially when taking into consideration the way America was turning thanks to this family time backlash. It's impossible to say if the show caused it or just rode the wave... it was just too popular not to have an effect, so deeply woven into our collective fabric it could not be torn out or considered objectively.

At the time this third MASH --the Col. Potter - BJ Hunnicutt seasons-- began it was still the mid-70s so the decadence of swinger suburbia was still in flourish, but by the time of the early 80s slasher boom, which as you know shattered me to the core, we clung desperately to such stalwart characters as old cavalry horse doctor Sherman Potter. Whereas Col. Henry Blake stuttered and hem-hawed around the generals and tried to deal with the Houlihan-Burns burr under his saddle by groans and evasions, Potter just dismisses them with a country witticism like "horse hockey!" and knows all the old generals on a nickname basis so easily kaboshes Houlihan's attempts to go over his head, usually. A 'career army man,' he knows the ins and outs, and has tolerance for Hawkeye and BJ because they're damn good surgeons, and they have a still back at the Swamp, so can provide him drinks after a tough operation; he's the first character to come along who makes the US Army look good - like they have some shit together to produce a fella so rounded, so Zen. His debut episode is great -- he starts out very suspect--no one knows if he's going to be a regular army buzzkill or cool like Henry. But by the end he's drinking and singing with the boys, and toasting old starlets: "Here's to Myrna Loy!" He won my heart all over again with that toast during this recent Netflix revisiting.

By season five it's clear M*A*S*H is now unremittingly wholesome, aside from the Burns-Houlihan thing --now constantly under threat from his wife (and officially ended when Houlihan meets and marries Donald Penopscott while away on leave) and Hawkeye and BJ are reduced to practical jokers of sophomore-level gaucheness. Father Mulcahy's gentle presence soothes and relieves; Radar's innocent sweetness lightens and warms; BJ's letters home to Peg and Col. Potter's letters home to Mildred lap into high tide sentimental toxicity. Events that used to breeze by in a single masterful scene are now drawn out for the duration and the supporting characters drift off one-by-one until there's only the Hawaiian islander nurse Kellye, the frog-voiced private Igor, and an occasional black person trailing a very special episode about racism along in their wake. The kind of malarkey most of us overcome by high school seems to take the walk-ons and Burns whole episodes to face and resolve. And Klinger, who began in male drag going nutzoid from the stress, has moved into having more and more of a major character, a salt of the earth Lebanese waxing nostalgic over Toledo hotspots. All the sexy nurses are long gone. It's not even the 80s yet. But it will be. God help us.

By season five, all that's left is drinking, but then, too, the drunkenness falls away.

And then... Burns leave, and is replaced by the stuffy but not entirely dislikable Charles Winchester III and the one fly buzzing the joint still allowed to be an unredeemable shit is gone.

The only time a nurse gets lucky now is if her husband comes to visit but his regiment leaves at dawn. BJ smiles with his familial reassurance, and he's not about to judge, yet somehow we spreads a cockblock tentacle through every secret tryst-ing door. If a nurse is around then it's a very special nurses episode. Each character now gets a chance to prove their humanity but it has to go away in order for it to come back. Klinger enters and exits with the regularity of clockwork with his new dresses and harebrained section-8 escapes for a joke - he's the Kramer! He's the freak. He's the tops. He's the Mona Lisa, as he lets you know in song. When BJ finally 'slips' with a nurse he nearly writes Peg about it until Hawkeye has to restrain him --don't ease your conscience by destroying her faith. Gradually, as often happens, the originally large constantly changing cast (like a real MASH might be) narrows down to eight. In the end it's just Houlihan, BJ, Hawkeye, Potter, Winchester, and Klinger. A MASH with only four doctors and a handful of nurses seems rather absurd, and one starts to long for the more realistic crowded constant in and out of people that made the movie at least believable. The pandemonium was good for creating a vivid sense of we were there, but now it's just about "characters" we know so well they're like us! But dad, we're watching TV to get away from ourselves!

And worse: the jokes lose their subversive bite and get progressively more sophomoric and pun-based: "The only spirits around here are the ones we drink," Hawkeye says during the very special "supernatural" episode. "The spirits must be exorcised." / "Well, exercise is good for you." Alda, now directing some episodes, seems distracted as a performer and way too smitten with the hokey liberal malarkey afoot. His eyes don't glisten with the mix of joi de vivre, compassion-tempered wit, and sexual charisma that elevated the early seasons to the pantheon of greatness.

But then, as season six gets to the halfway point, the show finds a way to be mature as well as mawkish: a second wind 'we hooked up and lets talk about it and still be friends' 70s sensitivity arises. There's a sudden refusal to just ignore or condemn the peccadilloes that were just lusty fun in the Gelbart era. People started to hook up, at all ages and attractive levels, without feeling like they had to get married or write their spouses and now they don't do so, but that doesn't make those times invalid, or those feeling 'sinful.' We can see the bridge between the unbridled free love late sixties and the AIDS-scarred sexual brake slam that must come with the early condom 80s. And it's a sign that M*A*S*H is evolving that it can stop on the bridge and take a reflective pee over the side. Hawkeye hits a superior officer but before he can be brought up on charges, the offended officer is wounded and Hawkeye saves him; amphetamine, which my pharmacist dad assured me flows wild and free amongst doctors (those famous 24 hour shifts would be impossible without them) makes an appearance towards the end of season six in 'a very special episode' where Charles abuses them. Why the hell does their supply include a big bottle of them if Winchester's the only one who ever takes them? Very special episode! Let it go. The kind of forgiveness and validation the characters express suddenly applies to itself - from us. Our desire to condemn this new less ribald 'third' incarnation fades, even as its saints come tumbling down: Hawkeye's nonstop joking is growing obnoxious; Charles' villainy manifests itself overtly but never organically BJ's early puppy-super ego vibe begins to dissipate as he finds his own way (a little bit) into a complicated character: a hypocrite who preaches California peace but lashes out, physically, at anyone who suggests he might have a sprained wrist.

If you stick with these later seasons through thick and then, of course, the show changes, evolves, illustrates a profound humanism. It had the ear of the world, a huge ratings share, and it uses it for good. The laugh track--even the 'soft' laugh they used--vanished for the entirety of season eight, which in my opinion made the show suffer mainly due to the writing and comedic rhythms not eliminating the empty pauses after punchlines. Comedians not used to sitcoms tend to go for longer stories where they don't pause for punch line laughs at all, not until they get the audience slowly warmed up to where they want them. That's only natural, but it took MASH awhile to find the right balance: what they call 'single camera' sitcoms, like The Office, 30 Rock, Parks and Rec were only born in the last decade.

It's awkward for awhile, sans laughs, but then - once again - they found their way. By season nine the awkward pauses so ingrained in comedy shows have closed like sutures; now jokes overlap and build through mounting craziness; And even if gradually the writing becomes very 'whose Emmy is it anyway?" off-Broadway monologue-ing, we can't really fault them for wanting to get victory laps in while they can. And we love it when they occasionally reference past events from past episodes, sometimes even changing the memory, as memories do change... all in ways not common with 'stand alone' episode formats.

As the show began to stretch far longer than the war itself, or any doctor's tour of duty, winter after winter, summer after summer, the show became almost existential, as if there would never come a time when it wouldn't be war in Korea. So real life spilled over into the margins, and souls grew - what else could they do? Hawkeye was allowed to have his character weaknesses: always needing to be the center of attention, hyper-competitive, self-righteous --we see these unpleasant characteristics manifest again and again as the years drag on. BJ could get very violent, a mean drunk, and overly emotional and not apply the same rules of empathy to himself as he does others (like that old WC Fields joke where he's about to strike his child citing"no little brat's going to tell me I don't love her.") They all did their best to save lives, but sometimes even risking the lives of those around them, as when their self-righteous worry over enemy wounded's safety allows for a vicious North Korean guerrilla female in their post-op to almost kill the other patients and even try to kill those who help her, several times over, and not only do the doctors refuse to stop helping her, they bite the hand of anyone who tries to restrain her --in this case a South Korean officer (Mako) planning to take her away for interrogation. Even so, they don't admit they're wrong--even after she spits on them for being fools. But the audience is certainly allowed to agree with her, and to perhaps understand that the very same compulsive compassion that makes good doctors can have brutal collateral damage on those around.

Radar leaves. Klinger takes over his job, goes back to wearing khakis, is promoted to sergeant and picks up a new trait: he starts trying to constantly find bizarre ways to make money using the army's surplus, bad puns and jokes like "the Two Musketeers" for the abridged version (cheaper). And eventually who the hell knows? They run out of war-specific material so start to recycle sitcom-ish plots and life lesson illustrations from all around them, and everyone's boasting of immanent satisfaction via some trip or scheme which --like Gilligan rescues--always seems to ensure subsequent failure and dashed hopes--Tokyo is canceled, here come the choppers!

One thing's for sure, we're reminded again and again that eccentric steam-letting is all forgiven if you deliver in the O.R. It's not too difficult a trade-off to understand. But they sure do stress it.

Every so often there's a profound connection to life, its frailty, its be-there and goneness. Every so often there's a 'doctor heal thyself" episode. Houlihan gets all platinum blonde feather haired and perennially sunburned and we sense her awareness of her status as a sexual icon of the day, right up with Farrah Fawcett Majors as far as popularizing the wavy long hair look which would then become the moussed up pouffy perm of the 80s. Season 10: the laugh track creeps back in; it comes and goes with a USO tour, "Colonel Potter is a verily happy married man!" - "So were my five husbands, until they met me." The laugh track disappears again later the next episode but the rhythm of the comedy never wavers, it moves into people not leaving space between speakers for the laughs, it becomes a kind of near Hawksian rhythm and develops more community, so the laugh track is organic, even subliminal. It sounds less canned and more like people trying not to laugh, under their breath, keeping it low to not disturb the set or something, which works very well.

They get excited by a new gadget called a Polaroid camera and it becomes a "shutterbug episode" with Potter reminiscing over pics he took of Mildred. And then there's regular occurrences of camp thieves. The whole camp (all eight of them) get excited over a newspaper! Ir's the 'mail episode' or the competition over who gets to use the camera. But it's stolen! A whole series of unfortunate coincidences hook Klinger into the clink (that kind of humor).

By now the camp is so small and normalized they're all like one large family - aside from the gravel-voiced Sgt. Rizzo there's no more recurring minor characters, with all the nurses being more or less represented by Nurse Kelly. Hawkeye's philandering is now down to a series or rejections which he seems to bring on himself by coming on too strong and direct and jokey, like he'd be terrified if one of the girls he asks out ever says yes. If there is any flinging going on, it's kept far from the camera and if something happens, it's then talked about, resolved, old vows renewed, the interloper let off gently. The trial of Max Klinger, who 'stole' sixteen bibles from some hotel (like that's even possible, or there's a market) makes no sense. There's never a shortage of bibles. Do Baptists track you down when you take the one in the drawer, not that anyone does? That's why they put them there. But I mention it as indicative of the way Fordian sentiment has crept even into the subterfuge. Between Mulcahy and his dumb Christian kindness, Potter's homey witticisms, BJ's ever-shifting mix of blind self-pity and caged fury, Houlihan's bluster and shaken poise, Winchester's snobby classical music blaring and refusing to share his epicurean tidbits from home, and of course Klinger's scamming, the show ensconces itself in a familiar trench rather than advancing over open ground in a forward Patton-esque charge ala Larry Gelbart's original vision.

Later on in season ten it's like the ninth inning of Bad News Bears, when Matthau finally sends in all the losers, so shlubs right and left get to direct episodes. Everything sounds like weak ass Thornton Wilder, or any number of anti-war tracts from the FDR New Deal. Houlihan does a great modulation from bitchy sober to confessional drunk; like a friend we know and tolerate as she comes back again and again to the source of her woe, a feeling of rootlessness the result of being an army brat, forever on the move. But time and again she has to be isolated in the wild with one other person, Klinger, Hawkeye, Trapper, and a bottle to let her hair down so to speak. Patrick Swayze is a loyal buddy praying for his pal's recovery; Larry Fishburne is a victim of Tom Atkins' racism; reliable actual WW2 combat veteran and Fuller's star of The Steel Helmet, Gene Evans is an embellishing war correspondent; Pat Hingle is an old buddy of Potter's; Linda Lavin does an alcoholic nurse who gets hilariously sudden and unrealistic DTs. And on and on into the infinity.

Season 10 begins and ends with some laugh track. Father Mulcahy is all excited about some incoming boxing champ. The peddler sells Klinger a goat and he starts selling fresh milk. Someone steals the payroll. "That's the third compliment you ever gave me," and a lot of bickering- that was no chicken, it was a babyy! oh my god!! Alda's never been entirely convincing in these big Sidney breakthroughs, but he tries, god bless him; and then 'Goodbye' - we were all pretty bummed out by that ending - "goodbye" - what the hell does that mean? Does it relate to something he said earlier in the episode? How are we supposed to remember that tiny fraction of an exchange between them so far back either in the episode. It's a two hour finale - no one's going to remember something that early. Goodbye, indeed!

CONCLUSION

In some ways the North Koreans are still being fought today, and this show lasted more than thrice as long as the "official" police action, i.e. war. It went from edgy, ribald sexual openness to Apple's Way-Waltons esque moral lessons, presided over by the ubermeek chaplain, androgynous corporals, sporadic jaw-dropping incompetence in order for competence to re-manifest like the second coming; family matters, children being delivered nearly as often as wounded treated, terrible puns and every gun a lethal weapon in the hands of children. A possibly endangered Houlihan as the subject of comedy; a life hanging in the balance as Radar tries to pretend he's made uncomfortable by investigating the ladies' shower. Hawkeye devolving from ladykiller playa with a different nurse every night to a celibate pervert who prefers nudie magazines and peeking into the girl's shower, rattling off the kind of lame double entendres losers use when hitting on a girl they know will reject them. Of course I left a ton of things out. But I said my piece. Now that all the episodes are on Netflix (and the finale isn't there but you can find it online), I heartily recommend you revisit the show in the original chronology, something we could only dream about at the time. Taken together these 255 shows are the War and Peace meets Duck Soup of our time. And in the first seasons especially, Alan Alda is a god, and his comedic rapport with Trapper so alacritous it's never been equalled. As a hardened ex-swinger myself, all I can do is look into those twinkly eyes of Hawkeye and realize he was my older brother, and the show, even in the third incarnation, a priceless work of American art, a key piece of our pop cultural psyche, perhaps as responsible for the sensitivity and liberal thinking of the 70s as mousse gulags were to the 80s. See the entirety of it on Netflix and know how white liberal America once most liked to think of itself: fluid, open-minded, and ready to heal every wound it made.

My sister and I grew watching the MASH reruns and we always defined episodes as either Trapper or Post-Trapper.

ReplyDelete