Caught THE SHINING (1980) for the 18th or 10th or 100th time Tuesday (!) and noticed new things (!) as always--the vast disconnect between the members of the Torrance family; how badly each is trapped in their own unconscious minds' grips; how the Overlook's trans-dimensional gravity widens the space between them into uncrossable gulfs. I also realized how a post-structuralist malaise hangs over the Overlook, making even normal job interview blather cryptic and enriched with mantra-like repetitions which I have to assume are a meant as vain buffer against the madness of irrational experience. Of the entire cast, only Shelly Duvall's perky mom uses words in a direct, emotional manner, and everyone but Danny thinks she's a rube because of it. I also gleaned new insight into cabin fever and the archetypal meaning of the bathroom. So come with me, neighbor, I don't want to be alone. Trying to retrace steps is as dangerous as going forward.

Cabin Fever is something we know very little about since scientific inquiries into its nature are difficult. The presence of the scientific observer alone is enough to stop it from manifesting. Checking on an isolated subject's door with a questionaire in hand can either snap the subject out of it, or put the knocker at serious risk. This is because the condition infers a complete collapse of the social sphere. Without anyone to bring the subject back to a consensual reality, the sufferer can't tell the real from his imagination. The visitor can be misinterpreted as any kind of demons our unconscious can dredge up. Because the space of the hotel is so vast the Torrance family each falls into a separate madness. With no direct link to the social order present to keep them anchored--whether to each other, the social order or linear time/space--they dissolve into the archetypal time warp created by their own unconscious minds; like an iPod that must erase its current contents to connect with a new hard drive (they're not called 'torrents' for nothing!) Danny is erased from his body altogether, to be replaced by his talking finger, Tony. Jack--in his writerly determination to not be 'a dull boy'--is compelled to literally sever his family ties so he can escape into the past. Shelly's inability to get a 'normal' response from either of the Torrance males drives her into hysterics, and when even her ability to check in with the Rangers station for a dose of consensual social reality sanity is cut off, there's no new hard drive waiting to fill her memory. For whatever reason, her social connection won't erase, leaving her alone to witness the full horror of the Overlook.

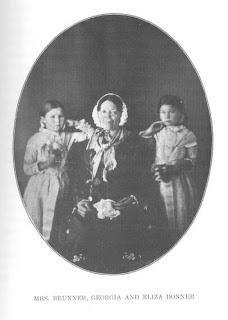

Consider their example in light of the quintessential cabin fever victims: the Donner party (mentioned by Jack during the family's car ride) who spent months starving and shivering in clumsy brush sheds, buried under mountains of snow, weakened by frostbite and starvation, with only some human remains for food. Several of them lost any semblance of 'sanity' simply because the situation itself was without any 'anchor' of space/time and social strata. In such a situation, sanity becomes a burden, an anachronism. We can read the accounts of the survivors, but it was not a time wherein people waxed on about their mental states, unless they were novelists or well educated.

In a way the relationship between Bowman and HAL in 2001 is reflected in THE SHINING, with its random markers "Tuesday" and "8:00 AM" indicating the complete breakdown and meaninglessness of time. There are no weekends in space, or at the Overlook, no intruding signifiers of social order for your madness to wriggle against. No alarm clocks. No recourse, except to kill any person whose reality might contradict your own.

Post-Structuralism - The second thing that stuck out this -nth viewing of THE SHINING was the constant repetition of 'tour guide' language: Jack and hotel staff (and later rangers via short wave radio) hide behind repetitive phrases ("sure looks like a lot of snow, over") and Jack especially clings to this repetition in his avoidance of any real commitment to his writing - his mantra of All Work and No Play make jack a dull boy functions as the endgame of a long string of repetitions heard throughout the film. Avoiding any genuine emotional connection to his family, Jack 'hides' in language, depending on his post-structuralist 'wit' for melting away the terror of any unsignified remainder that may come his way. But eventually, these mantras all fall by the wayside; they are feeble tools compared to the vast arsenal of symbolic language employed by the unconscious.

Note that the ghost bartender Lloyd (right) appears at Jack's big moment of crisis - when Shelly Duvall accuses him of hurting his son and Jack goes a little mad in outrage. Here he's wasted five months not having a single drink, out of some dorky fatherly guilt, and all for nothing as he's accused of hurting Danny anyway. His language finally breaks up a bit from the mantras and he mutters he'd sell his soul for a drink. There Lloyd is, without a word. Salvation and destruction all tied up in a single bargain. His statement "I would sell my soul for a drink," is perhaps the only 'true' thing he says, and as such constitutes a deal-done in the saying; the devil springs right up with full bottle service. Jack's eyes widen and bug out as he talks with Lloyd and the other ghosts, but he never dares ask anything like "are you real?" for that would risk sounding as square as his wife.

The Bathroom - Ground zero when it comes to realizing the drugs are kicking in. Check your dilated pupils in the mirror; freak out when you close the medicine cabinet and see a figure standing behind you, or a different background than the one you came in with; the toilet looms alien with its gaping porcelain maw of porcelain and swirling reflective light-off-the-small-square-tiles serpent scale vortices. This is the place of hair combing and judgment and bereavement, vows made to never drink tequila after wine, and last looks before you return to the merciless world of co-ed living. It is the place where coke moves from the tip of someone's car key into your nose, or you sneak cigarettes, or find the gun taped to the back of the old-fashioned toilet. We all surely know the 'boost' we may get when we break from our navigation of precarious social situations and retreat to the mirror of the bathroom to check our hair and psych ourselves for, and recover from, the million and one pressures, anxieties, and rewards, of social interaction. Here we are able to reconstitute our ego, a little mini-resurrection. The bathroom is where we go to delude and denude. We are allowed 'privacy' there, so can be naked without shame. And, as the hotel Overlook is so immensely private, the bathrooms in the film (there are two) are therefore double private, the haunted bath nook in room 237 is even a room within a room within a room, so triple private--so private that there is no difference between its reality and the realm of pure unconscious, and the tub is in a nook at the infinite point, for yet another layer--the mirror in the mirror room at the end of time in 2001. Time and language drift away in the solace of the gleaming fixtures and tiles, which correspond perfectly with our visualizations of the the drainage portal that lurks at the bottom of our souls, between our own unconscious and that of the universal collective, which is always waiting to back up the pipes and flood the room.

|

| From top: Psycho, 2001, The Holy Mountain, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me |

I've always felt if therapy wants to be truly effective it should take place in the bathroom. The room wherein the dancing dwarf speaks backwards in David Lynch's Twin Peaks is 'kind' of like this bathroom, a little less functional--like the outer lounge antechamber in swanky hotel ballroom bathrooms where you adjust your bow-tie at weddings and the dancing dwarf brushes your shoes and has a basket for tips and speaks in some indecipherable language. The beginning of Jodorowsky's THE HOLY MOUNTAIN takes place in a similar kind of bathroom/ tiled space, as the shaman shaves the heads of two women acolytes. This latter example evinces a superb understanding of the fantasmatic - with the hair shaving representing a complete identity melt (see also Kubrick's opening haircut sequence in FULL METAL JACKET) as an essential rite of passage when undertaking the trek to total self actualization and surrender.

In a Jungian analysis Jack's room 237 bathroom scene is something straight out of Hansel and Gretel - with the bathroom as the gingerbread house. Jack is a nervous but horny Hansel, the initial stern leggy sexiness of the female apparition is his candy. The breadcrumb trail in this case is the maze-like paths of the carpet and hallways that seem to pull him, like a magnet in slow dream time motion, towards the the woman, who is old witch and leggy candy rolled into a one-two switch. In Jung's lexicon, this old witch is the undernourished and most cranky shadow/anima, the 'wrathful deity' in the first bardo, the flip side of the peaceful deity / sexy young woman. Jack should have read the Tibetan Book of the Dead.

To get back to cabin fever, anyone who's been to the psychedelic mountain will surely have some chills of recognition in 237, for the room itself has cabin fever-- everything is slowed like clockwork and, without a 'majority' rule of perception to block the infinite with their tunnel vision reality, it's as if the Overlook is a galaxy and 237 bathroom is a black hole, through which one is drained into the pipes of Aboriginal 'dream-time.' One moves through the pipe and comes out of Marian Crane's open dilated pupil in PSYCHO, or out of the pistol barrel fired into the camera of Mick Jagger's brain at the end of PERFORMANCE. This small black hole slows down the world around it in an inescapable clockwork pentameter; hypnotic in its steady unwavering mechanical rhythm; it is the earth, the sun, and the wheels within wheels revolving in 2001's spaceships or Ezekiel's wheels in the sky. The drones on the soundtrack work to achieve this revolving sense of hypnosis, as does the slow, dreamlike movement of the camera and actors, the repetition of certain words over and over as a tool of hypnosis - "gimme the bat!" for example, becomes a mantra, as does 'redrum' and 'my responsibilities' and "Danny! Danny boy!"

Post-Post Structuralism - In my past viewings I've found her unbearable, but I came to respect and like Shelly Duvall's character this time around. After all, she does knock her husband out with a bat and then lock him in the pantry. She defends herself with a knife and eventually triumphs over him in every respect. She fucking kicks his ass! Her kid may be a nutcase and her husband a smartass but Shelly manages to keep some kind of grip on things even as she herself begins to see the apparitions. I was particularly aware of the wincing of the men over her gushing naivete during their initial tour, and it's that which clued me into the post-structuralist aspect: "This may be the biggest, most beautiful place I've ever been in!" she beams. The men wince at her guilelessness. Jack would never admit the Overlook was the biggest place he'd ever seen, lest he look like a rube whose never left Denver--and in part that's why he got the job. But its Shelly's kind of uncomplicated normality that survives cabin fever, not Jack's cynical melting clock-style evasiveness.

You see, you see Jack plays the game wherein all language is double filtered, repeated and used as a distancing tool, a way of negotiating one's way through matters too vast and complex to adequately sum up. For those who operate in this 'adult code' any gushing or exclamatory phrase pollutes the bond that acknowledges the power of the unspoken and is therefore evidence of immaturity --the domain of the squares, i.e. the wives who don't get invited out to drinks or the kid who knows you're tripping at the art opening and has to tell everyone so you can't 'pass' for sane as you would like. "You know he's tripping, right?" - "Shut up Max, I don't want them to know," -- "why, are you ashamed?" But tripping you can't even process the word ashamed, it's only that your enhanced depth perception has now been pinned down to a mere drug signifier to which most people have only one response, to rapidly move their hands back and forth on either side of your head and say "you're going down a tunnel whoosh whooosh!"

For speech to be 'successful' as indicative of one's adult insider status -- too cool to care, as it were-- said speech must circumvent and sidestep and 'double-time' its actual meaning, and protect the sublime in fields of repetition and banality. (Max should have said "Did you know he's not tripping? Isn't that wild!") The words Ullman speaks to Jack during the interview, for example, he's clearly spoken before, but he trots them out like a favorite old horse around a familiar well-worn track. The past murders are mentioned with the 'customary' tact and Jack reacts in just the way one would ideally react, without real thought or emotional surplus. Compare his reactions to someone who attempts to be 'earnest' when faced with a similar situation, and you know I'm thinking here of the meetings between Barton Fink and Lipnick (read my thing on that thing here)

|

The only way saying something is great without making it less great is if the great thing has moved safely into the past - which is part of why the bourgeoisie prefers their artists long dead before they honor them. The artist was great but can never be great in that moment. (Jack is finally happy when he is 'already dead' and appears bottom center in the 1921 photo (above) his arms contorted like a Satanic puppet.

Jack triumphs because he never weakens in his mastery of repetition in language, he's like a horror icon version of Warhol. In repetition only does language prove an equal to direct experience, and only repetition can actually 'enhance' direct experience by hypnotizing the conscious mind into a state of strictly observational stasis. Approached via mantra, by removing one's focus from the realm of the symbolic, by repeating a single word over and over until it loses all meaning, the obscene dimensions of the real are suddenly exposed. Say it enough times in a row and even the word 'beauty' becomes a hideous, trumpet-like mass of snouts and tentacles. Better just wait in the bathroom until these tentacled noises have passed into rusty memory and silence removes your last few senses like barnacles and all tomorrow's parties are safely receded in the tide.

I believe you just blew my mind, sir.

ReplyDeleteBest review yet. That Kubrick, whataguy

ReplyDeleteBeautiful review Erich

ReplyDelete