Ever ready to use seduction or a mixture of the kind of martial arts (Muay Thai, Kali, etc) that involves swinging around people's necks like an ice ballet starlet, in Ghost in the Shell she also has a great 'across the thug-filled room' saunter, shoulders low and hunched, as if primed for a sneak attack, and a unique way with sussing potential trouble out of the corner of her eye without breaking stride or cool. She seems always a notch above her material, yet she doesn't step on its toes as she climbs. Gingerly she even brings it along behind her. No easy feat, to redeem and solidify shaky CGI realities. It's OK, too, if she can't quite pull off some of the more encompassing moments of grandeur, for she has the brains to underplay rather than ham it up. Hers is the same cool savvy of 80s (male) action stars like Bruce Willis and Arnold Schwarzenegger --if she lacks their self-deprecating doofus undercarriage, she at least doesn't wink at the audience or start doing funky dances like Cameron Diaz. That shit doesn't age well (just watch those two Charlie's Angels movies, or Knight and Day), but Scarlett is built to last.

Though adept at smaller scale comedies (where she'll occasionally dust off her Jersey-Bronx-LI accent), since becoming an A-lister, ScarJo hasn't labored for respectability in prestige pics too often, content instead with her lot as the poster girl for a Tyrell Corporation-sponsored Time-Image sci-fi future. The first girl to hang glide all the way across the Uncanny Valley, she's part Hawksian 'one of the guys,' part 'your older sister's one cool friend who's nice to you.' When we see strange new sci-fi worlds through her eyes, they seem livable; their furrowed scalps are gently but robustly tousled by her maternal (but not bossy) fingers. Be they Seoul's skyways, the post-riot despair of 3 AM Glasgow, jet-lagged Tokyo, futuristic Tokyo, some other Tokyo, Paris, mall culture America, the empty rose-colored void, she can bring humanist warmth.

Turn on any channel and there she is, making the future seem not only real, but inviting, even survivable.

|

| Her gaijin hair is Asiatic hipster grrl cool. (Ghost in the Shell) |

I'd heard the 'white-washing' accusations (1) before going to (open the Netflix envelope of) Ghost in the Shell, but that only helped lower my expectations, which were low to begin with, for it seemed like Aeon Flux meets Ultraviolet x Resident Evil all over again. But after seeing it I was a fan. Ghost in the Shell is actually a goddamn great film. It's so rich in ambient futuristic detail --from the ingeniously animatronic reptilian geisha girl assassins to the visualized 3-D streams of bit data (they make the green columns in The Matrix seem like the dos prompts in War Games --insert snorty nerd laugh)--its generic cop vs. corporate corruption clunkiness is forgivable (and certainly no more perfunctory than that in Ghost's most obvious template, Blade Runner) and maybe even necessary, since the mise-en-scene itself is so densely layered we need the story to be familiar enough we're not totally alienated.

In a role originally played an anime pixie (and ink has no race, people!), Johansson stars as "The Major," an advanced cybernetic cop chick chassis (the shell) housing a Japanese girl's ghost. Fronting an elite group of cops, she investigates AI-related crimes, and is a bit of a hothead. She regularly gets told not to rush into danger by her concerned chief (Takeshi "Beat" Kitano), which is almost as tired a cliche as M. Emmett Walsh tossing back whiskey and cigars while talking about "beauty and the beast - she's both." As in Blade Runner, some advanced robotics engineers are the target of a splinter group of amok replicants, or something (shades of Shelley!). Their next target seems to be Major's own creator, Juliette Binoche (which is funny if you've just seen Clouds of Sils Maria).

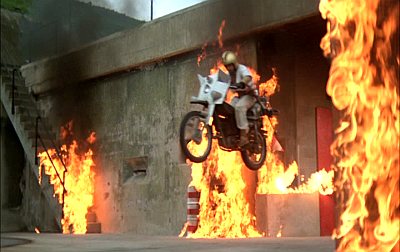

(Spoiler Alert!) The killer /bad guy, 'Kuze', a cyberterrorist robot-human, played by another gaijin, Michael Pitt, is a marvelously intricate character in both acting and CGI senses of the word. he seems to be constantly reconstituting himself from surrounding bit rates, only half alive and half virtual at any given time, his tortured voice wracked with auto-tune and static, his awareness of his past at odds with the Major's computer generated amnesia. Once they start talking, Major starts 'going rogue' while the evil robotics CEO turns the bullets their way. Luckily, the cool thing about being a robot: she can get shot to shit and still be ready to dive slow-mo backwards off the parapet and come crashing upside down through a skyscraper window with both automatics Woo-style blazing in just a few dissolves. The future is nothing to fear as long as hangdog toughies like Beat Kitano carry teflon briefcases and can shoot from the hip. It's an unusually upbeat, even tidy, Robocop style resolution, but it hardly matters - the greatness is in the details, the startling HD clarity that makes the film seem ready for a VR headset 2020 remastering. Compared to the new Blade Runner movie, it's a goddamned masterpiece - maybe even better than the original Blade Runner or, gasp, even Akira! Time will tell.

In her hirers defense, ScarJo has ample experience for the job, including that of being alienated in Tokyo (as 2003's Lost in Translation); having her face dissolve into bits of digital programming, also in Tokyo (in Luc Besson's Lucy); disappearing altogether and becoming just a SIRI-style AI voic (in Spike Jonze's Her); growing up as a rich person's clone, for future organ harvesting in a Logan's Run style enclosed citadel in The Island - etc. I'd also say that, though white-washing is a long and shameful cinematic practice, Boris Karloff and Christopher Lee didn't just play Fu Manchu because they were white, but because they'd played evil megalomaniacs successfully in the past. Fu is more than just Asian - he's also evil and a genius. Those three things are not always interconnected and in dicerning Fu's chief trait as his Chinese decent one does China a disservice as much as the other way around. In the same way, ScarJo the actor has a resume of successfully conveyed artificial intelligences, test tube babies, amnesiacs, assassins, and substantial fight training that keeps the obligatory hair in the face stunt doubling to a minimum. She's a global star. She's sanded her psyche down for mass appeal, ready to be on the cover of everything from Italian Vogue to Japanese iPhone keypad ads for fragrances based on the novelization of the German film based on a Chinese fable.

There is one way to avoid all the conflicts when watching Ghost, a way to amp up the subtextual resonance until it rings like freedom's bell: watch it on Blu-ray with a Japanese dub language track. Hearing a Japanese actress speaking from inside ScarJo, as a Japanese ghost trapped in an artificial gaijin shell, will likely make all the difference.

I don't know why I'm sticking up for the casting decision- except that I, like everyone else of the SWM variety, needs to prove he's not racist, even if it's only to himself, and the filmmakers clearly went for distance in re-imagining both their holy bible Blade Runner and the original 1995 anime classic. There are multiple viewings worth of layered space and evocatively wrought Black Mirror future shockiness, and I'd hate for all that to be lost like tears in rain just because the producers were scared Maggie Q. wasn't enough of a household name. The level of artistry and detail on display is jaw-dropping, and for once it actually serves a narrative purpose: cluing us in on--not only the world of a very conceivable, maybe even inevitable, future--but the foreign/alien way that future will be perceived, i.e. when VR and 'R' merge inextricably.

I can hardly wait until it too is on FX or FXX and comes punctuated with commercials for 4D, the 'next word' in high-definition television. Ghost in the Shell seems clearly meant for it.

As an anime from 1995, all its cyberpunk detail often seemed to get lost in the overwhelming rush of negative and positive space (ink can't be layered the way blacks shadows in HD can) and--let's face it--the internet was just getting rolling in '95 --AOL still connected via whirring phone modem. A lot of all that internet stuff was still just on the (printed pulp paper) page of Phillip K. Dick and William Gibson novels. Shell's anime style (left) used a lot of rotoscoping and 'real' lights and--unless you were an anime devotee familiar with the narrative tics and traits, ahead of the curve on the dawn of cyberspace--it seemed a kind of over-the-top cartoonish reliance on animation shortcuts rather than segue/linking micro-movement (i.e breathing). That over-the-top literalness in this live action version lives on only in the 'tactical' eye adjustments of Batou (Major's right hand man, he loses his human eyes in a bomb blast, and opts for two telephoto / infrared lenses that make him look like Little Orphan Annie's jacked uncle). Aside from that, nearly every image is sublime and best of all, at least semi-subtle and subdued. Since the actual actors and lighting provides some measure of corporeal relativity, the VR super-impositions stand out yet are so fully meshed, at times reminded me of last February when I had the DTs. While the slow-mo glass shattering and frozen water diving splashes have long been cliche (thanks to The Matrix), here they actually fit the post-modern future on display, as she comes through a window that's also a giant video screen - as if turning the pixels of the image into glass shards.

The ultimate takeaway is that, when the virtual world is as valid and 'real' as this one, (and the Uncanny Valley bridged), one of the side effect developments will be time travel along personal axises and the ability to replay our sensory recording of a single event, which can then be slowed down until the whole world stops on a fraction of a nanosecond for all eternity, and those watching/reviewing can wander into the middle of your 3D retinal projection display and see around corners and read the names of files left on the dresser. Weirder still, these memories could be hacked, so that around the corner too might be a VR assassin ready to--if not actually stop your heart and kill you--at least steal your mental capacity, leave you a stunned amnesiac while he makes off with your internal hard drive. We see bits and pieces of this future in various Black Mirror episodes, but here it all fits together in a blast that's like an atomic bomb trapped inside an orchid.

If social-racial progress gets knocked back a peg by ScarJo's presence in this film, beauty parameters takes one step forward due to her lack of fear at presenting to the world a genuine womanly shape in bodysuit --not zaftig or shapeless mind you, but filled out like a mix of Marilyn Monroe and a UFC fighter -- her lower center of gravity and sinuous synchronized shoulders and pelvis betray evidence of long-term fight training ala Cynthia Rothrock in her earlier films and of Gina Carano in her current ones. She keeps her head perfectly balanced, like a Steadicam, when she weaves around a room, shoulders slinking cannily back and like a combination alley cat and see-saw.

It makes a huge difference. Watching Rothrock throw down next to Michelle Yeoh for example in Yes Madam! is to see the difference between a dancer, lithe and fast (Yeoh) and a genuine kickass fighter (Rothrock); Johansson has grown into the latter. You just can't imagine yourself getting back up from a fight with ScarJo as easily as you can one with Maggie Q.

At the same time, Johansson's modulated low-key acting (as demonstrated first in Lucy) fits both this fighter stance parameter and the role of a soul who's basically had her identity stripped away; her brain has been washed white and enhanced with micro-processors that record and play back memories that can be, as in the Tyrell corporations' most gifted Nexus edition, Rachel (Sean Young), artificially implanted or removed. Her whiteness and blank performance reflect cultural meaning in an era where the digital and analog are no longer separate, where humans can be hacked and turned into weapons just by touching the wrong door knob during a live action interior chip role playing game. But it's her daringly 'real woman' body, unhidden and unashamed, that becomes the unassimilable remainder, an assertion of humanity against the machine, and her micro-gestures of awakening vulnerability accomplish a gravitas Sean Young never could.

What makes Ghost in the Shell work for me, too is that, like Blade Runner, it keeps its ambitions and goals for narrative resolution low-- cliche'd, linear, resolved--to better focus on the visuals, mood, ambience and subtext. Compare with, say, the disastrous Matrix sequels where vast reels trudge across with abstract thesis dissertations on the collapse of space-time vs. the simple Wizard of Oz meets the Pusherman mythos of the first. Macking out between the cop show beats in Ghost are fascinating throwaways, such as a go-nowhere but still interesting scene where she touches the actual flesh(?) of an androgynous, only partially-human, 'mixed race' freckled prostitute (above). In a very touching--but not quite sexy--scene their faces touch close enough the heat is there, but there's no need to go all the way into some gratuitous cyber-lesbianism. Instead we have that curiosity with which a human might gaze into an animal's eyes (as in the cliche'd scenes with Batou's stray mutts) or vice versa, each fascinated by the mystery of a separate, never quite-knowable intelligence on the other side -- as beautiful, as de Lautréamont's saying goes, as the chance encounter between a sewing machine and an umbrella on the dissecting table. For Major it's the unknowability of what makes us human, metered out with the fascination of the machine for the human and vice versa; each enraptured, envious, even, of the other: a human with artificial augmentation seen through the eyes of the reverse.

And then there's the weirdest, most strangely vivid and human--portion of Ghost in the Shell: Kaori Momoi a Major's mom. It's clear English is not Momoi's first language but she attacks it with a stunning, raw innocence- as if in forming these strange words she's creating some new kind of polyurethane fiber: even across the divides of language and digital artificial shell recombination, and even race, she quickly recognizes her long lost daughter without ever having a big reveal. Maybe we can all learn a lesson from that. Probably not.

IRON MAN 2 / AVENGERS: AGE OF ULTRON / CAPT. AMERICA: THE WINTER SOLDIER: BLACK WIDOW needs her own damn movie, Marvel.

A nurturing friend to the Comic-Con geek, ScarJo likes to get right up close to the Hulk and rub his fingers or invade his puny Banner's personal space, or fall on top of him in a sexy silk dress behind the bar, telling him "don't turn green, ok?" She ends up trying to help Capt. America find a girlfriend even while they unfurl a dastardly Fourth Reich Paperclip conspiracy deep within the CIA (I mean HYDRA within SHIELD) and finally does the direct approach with Banner when he won't take please for an answer, and he ends up running away instead. The smart move, that, because Black Widow is single for a reason: Marvel 'gets it' -she belongs to us all. She's who we, the lovelorn teenage male demographic, imagines coming home to. We know she wouldn't be turned off by our living in mom's basement and spending our disposable income on mint condition action figures. Were Marvel to saddle her up with some dude like Luke Wilson, bringing her flowers and making hangdog eyes, that, sir, would be a major miscalculation in how fantasy works to allay and soothe the hormone-tortured adolescent mind.

Marvel's too smart for that. Marvel gets it, and clearly posits Black Widow (it's in the name) as the girl we can imagine ourselves with (lord knows I did, back in the days of her character's large-size black and white comics when I was at a nerdy high school freshman). Or at the very least she stays single and we stay best buddies.

Marvel's too smart for that. Marvel gets it, and clearly posits Black Widow (it's in the name) as the girl we can imagine ourselves with (lord knows I did, back in the days of her character's large-size black and white comics when I was at a nerdy high school freshman). Or at the very least she stays single and we stay best buddies.That said, I wonder just how many young boys and lesbians actually do imagine themselves with Scarlett Johansson. I don't think it's that many - she's more like our badass fantasy friend. Maybe it's her Bronx upbringing, but Scarlett's one weakness is that she can't do 'weakness.' She can never quite tap the accessible vulnerability (emblematic in, say Heather Graham or Patricia Arquette) that brings out the lusty aggressor in a man, so essential to his sex drive. Instead, we love her at a respectful distance, and like her style; as a pal, she boosts our ego without having to get awkward about it.

There's a scene early in the first Avengers where she's tied up and getting slapped around by a cadre of Russian mobsters in an abandoned warehouse and her cell phone rings, it's Fury who wants her to come in, and she says something like Hold on, I'm almost done interrogating these guys. In the calm collected way she says it, the men realize she's never not been in control of the situation like they thought. She easily escapes her bonds and beats the shit out of them all with pieces of the broken chair, then sashays away. That scene to me illustrates the breadth of Scarlett's range, for she is not the most giving and exhibitionist of actresses. This scene plays her dramatic weaknesses into strengths the way Neil Young overcomes his limitations on guitar, through a kind of advanced depth primitivism. We can buy her as vulnerable only if it comes packaged with the idea it might be a ruse.

On the other extreme of the acting intensity range, for example, we might consider Noomi Rapace, who acts her pain and anger so vividly in films like Prometheus and Girl with the Dragon Tattoo that she leaves any concept of 'fun' far behind her. In her hands, that scene in the Russian warehouse would be a grueling drag. She'd make the pain and trauma of her slapping brutally real - she'd make it our problem, the post-Fury call thrashing would be cathartic but we'd still be left irritable and clammy. Rapace forgets we come to movies to be entertained, especially movies about space monsters and girl avengers. We don't need to feel traumatized, or to hate ourselves worse than we already do. The only thing tempering our pain at Rapace's automated C-section in Prometheus is that her character has been such a self-righteous drag we're happy to see her suffer. She makes her own pregnancy issues everyone else's problem, then gets pissy when the ship's crew don't drop everything they're doing to ram an alien space craft on her command even if it will kill them all. ScarJo by contrast implicitly understands the parameters of a scene in ways beyond mere chops and intensity; she's her generation's Angie Dickinson, she's Lauren Bacall x Alice Faye.

|

| Dig the way her shoulders hunch and move with her eyesight like a canny low-center boxer snaking through the crowded disco as the ecstasy kicks in. |

Good lord! Delivered by Johansson in a flat whispery monotone, Lucy's call to mom will bring uncomfortable recognition from anyone who's ever had a mind-opening drug trip / manic high and decided to call their mom out of the blue to re-'connect', and explain they've cracked it wide open, broken the code, that they 'get it now' and can see past the limitations of time and space and realize all the interconnected love etc. etc. This will either move their mom to tears of gratitude or have her ready to call the psychiatric clinic. I know I've had a few of those back in the 80s-90s, and was always grateful for my mom's sense of denial, for I'd never hear about it later and forgot most of what I said/promised. Since then, I've been on the other end, watching younger generations do the same thing and I've been privy to how crazy these sorts of phone calls and explanations sound, both pretentious and deluded, egotistical and full of fragility masked in bravado, as if in convincing me of their discovery their discovery becomes permanent, rather than just the flash of illumination - eternal only in the memory. It's like they try to etch these fleeting feelings into the consciousness of those around them, rather than where they should go- onto paper, magnetic tape, and hard drives- but, what might be trippy in art, brilliant in theory, sounds nuts in verbal rants to your sleepy friends and parents. Profound insight doesn't translate out of the blue, just like hearing about someone else's dream never has the same dizzy power as telling our own.

It's perhaps the sadder truth of enlightenment, especially via the poison path, that the more brilliantly the ideas cascade inside your mind, the more the tongue can barely keep pace. Ideas, insight and inspiration may all flow out into brush strokes on canvas, words on the screen, words from the mouth - but try to talk normal to a friend or parent and you don't sound like someone who's cracked it wide open and broke on through to the other side. You sound like an amok egotistical maniac, a frothing lack-of-sleep meth-addled grandiose version of James Mason in Bigger than Life and maybe, a little bit, like Scarlett Johansson in Lucy would if she didn't wisely underplay to such a dry extent. It may seem at the time like bad, flat acting, but any other way would be far worse. And besides, soon her Lucy can back up her words by remote controlling all media and gravity via telekinesis and shit in ways that make her more than a match for Neo in The Matrix, but she does it all without leather and dark glasses.

It's perhaps the sadder truth of enlightenment, especially via the poison path, that the more brilliantly the ideas cascade inside your mind, the more the tongue can barely keep pace. Ideas, insight and inspiration may all flow out into brush strokes on canvas, words on the screen, words from the mouth - but try to talk normal to a friend or parent and you don't sound like someone who's cracked it wide open and broke on through to the other side. You sound like an amok egotistical maniac, a frothing lack-of-sleep meth-addled grandiose version of James Mason in Bigger than Life and maybe, a little bit, like Scarlett Johansson in Lucy would if she didn't wisely underplay to such a dry extent. It may seem at the time like bad, flat acting, but any other way would be far worse. And besides, soon her Lucy can back up her words by remote controlling all media and gravity via telekinesis and shit in ways that make her more than a match for Neo in The Matrix, but she does it all without leather and dark glasses. |

| For Lost in Translation (see A Jet-Lagged Hayride with Dracula) |

|

| Ghost World |

Scarlett J. was right to do dump her because Enid's world view and attitude is, in the end, not self-sustaining. There's nowhere to go, and that--I think--was the film's big flaw, it didn't know how to end itself. It should have zapped the title up to a blast of punk anarchy when the old man gets on the bus that wasn't supposed to come and leaves Enid alone on the bench. Bam! She looks out at camera, Bam! Ghost World title card and punk rock credits music. Kafka-esque, man: the bus out of here never comes - oh wait it came after all these years - and now it's gone again! Forever! A Winner. They probably tried that ending, but test audience asked what happened to Seymour, so the film checks in with Seymour again, letting us know--not that we cared--he's doing just fine, getting professional help, as if we needed to know that rather than to experience his and Enid's fall both in that one bus stop moment. The utter pointlessness of rebelling against life outside the beef jerky and nunchucks of prefab American reality while still living within in it, Scarlett mutes it all down and gets excited about a fold-down ironing board in the apartment she's renting with Enid (if Enid gets the money), and that's really the film's one emotional payoff. The terror that flits across Enid's face as she suddenly realizes she truly is alone in the universe. Bam! Ghost World title card and punk rock credits music. Another key winner final shot.

This is the gaze that boys want to see mirrored back, for it acknowledges their gaze as something other than a toad-like imposition; even as it gently rejects, it flatters; the male gaze is returned without the Medusa stone surcharge so usually associated with 'real' women. The fanboy's gaze is not judged sexist, misogynist, evil, gross or all the other judgments breathing mammalian women make on men who leer way out of their league, nor is it returned with a come-on directness like a prostitute meeting their gaze across an Uncanny Valley casino bar, the type where you look away in fear instantly, before you consciously even realize what just happened. Even if you've never seen a high end prostitute in the wild, you still instinctively don't kick yourself for being chicken, because you suddenly realize a beautiful girl's sudden reciprocal stare is terrifying, your gaze can't help but flinch if it's not used to being gazed back at the same way that it gazes. It's like Delilah springing forth with a garden shears to cut your balls or hair off the minute you spot her in the Waldo crowd.

ScarJo doesn't bring the shears. Her stare says, hey man, relax, the parts of us that are human are so far apart I can look back at you as insolently as you look at me in the hidden darkness of your roost. The shell you gaze into may be owned by Sony, but my ghost is my own, and I promise you this: no matter what else the future may shear away, you can keep your hair on.

Further Reading:

Skeeved by an Asian: THE BITTER TEA OF GENERAL YEN, MASK OF FU MANCHU, ETC.

It's only real if it wrecks your life: HER, THE WAY WE WERE, LOVE AFFAIR

Antichrist in Translation: UNDER THE SKIN, HABIT

CinemArchetype 16: Automaton / Ariel

A Jet-Lagged Hayride with Dracula: LOST IN TRANSLATION, THIS GUN FOR HIRE

NOTES:

1. Blair, Gavin J. (April 19, 2016). "Scarlett Johansson in 'Ghost in the Shell': Japanese Industry, Fans Surprised by 'Whitewashing' Outrage".

Skeeved by an Asian: THE BITTER TEA OF GENERAL YEN, MASK OF FU MANCHU, ETC.

It's only real if it wrecks your life: HER, THE WAY WE WERE, LOVE AFFAIR

Antichrist in Translation: UNDER THE SKIN, HABIT

CinemArchetype 16: Automaton / Ariel

A Jet-Lagged Hayride with Dracula: LOST IN TRANSLATION, THIS GUN FOR HIRE

NOTES:

1. Blair, Gavin J. (April 19, 2016). "Scarlett Johansson in 'Ghost in the Shell': Japanese Industry, Fans Surprised by 'Whitewashing' Outrage".