Hey sweetie, let a man 'splain it for you: the 70s were a great time for feminist horror, though the word back then was "women's lib." It was all about being liberated --via sex, pills, books, grass, the sea, castration, and the occult, and violence, too! Paths out one's domestic bliss trap were varied and didn't all have to end in death or marriage. Horror movies latched on for the ride, but the trip would usually make the girl go Ophelia-level mad before she found she wasn't crazy at all: the whole world was a massive patriarchal cult determined to keep her 'down'. In films like Let's Scare Jessica to Death (1971), The Sentinel (1977) and Stepford Wives (1975) she's actually sane and everyone else is nuts (as in Polanski's Rosemary's Baby). In 1975's Symptoms, for example, it was the other way around (ala Polanski's Repulsion). But it turns out there's a third way (beyond Polanski's ken), where the woman is crazy and 'liberated.' Truly a product of her moment, far outside the reaches of conventional nuclear family values, she's a heroine for her times-- sweet as applejack with a kick that could geld a stallion at thirty paces. It's not traumatic though because the people around this crazy lady genuinely love her and are, more or less, normal, or at any rate, pleasantly debauched (you know, not a bunch of drags). There's only one film like that in all of western civilizations: Matt Climber's 1976 near-cult semi-classic, The Witch who Came from the Sea. It's not hard to guess why this film has never become a big cult classic it deserves to be (or why there's no Polanski template). But now, on Prime in HD and looking good, albeit slightly faded, there's no reason not to batten down the hatches, zip up to and delve into primal Freudian/Jungian chthonic murk so thick and rich it must be good for you to get this squeamish. If you're an ally, plunge in!

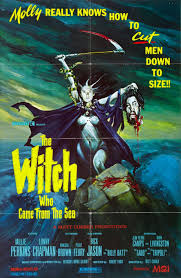

I'll confess: my squeamishness when it comes to seeing females abused in movies--even if the abused, or Liam Neeson, wreaks suitable cathartic vengeance--will make me avoid a movie altogether no matter how ubiquitous it is in 'the conversation' (I still ain't seen Last House on the Left or Irreversible). My Ludovico-induced feminist liberal arts programming is too strong for such imagery not to linger in my brain, tainting all subsequent media consumed by association; I have to write vast screeds on Bright Lights to vent about it just to breathe. So I staved off seeing Witch even though it's right up my alley (if you'll forgive the expression) as far as being pro-castration (I'm no militant, but I consider Teeth too sensitive and Hard Candy too soft). Imagining a depressing 16mm treatise on child abuse and dirty wallpaper (looking dour and grungy like Romero's Season of the Witch), I avoided Witch who Came From the Sea even though I've been long drawn to Witch's poster of a defenestrating Kali Venus, rising on the foam of the castrated lovers. So I was glad it showed up on Prime looking all engorged and gorgeous. I finally had the nerve to see it last weekend after coming home from Gaspar Noe's Climax at the Alamo, since I was already in shock (so knew I'd be, temporarily, invulnerable to further trauma).

Turns out, I had nothing to worry about. It rules!

It 'gets' it - the brutalizing way so much abuse is depicted on film clashes with the mind's ability to cover up unendurable experience in the shroud of dream and abstract memory. Thus the childhood trauma flashbacks are warped by cartoon and ocean sound effects and bizarre incongruous details that make it all too strange to feel brutalized by, instead the feeling is like remembering strange nightmares from childhood, too bizarre to be terrifying- the brain abstracting trauma until its palatable (and then splitting off a separate persona as a side effect).

Millie Perkins stars as Molly "The Mermaid," a single barmaid at a seaside dive on the beach of Santa Monica, "The Boathouse," owned and operated by the pleasantly grizzled Long John (Lonny Chapman). She's not just great babysitter to her two adoring nephews, beloved of clientele and employees, but she has the ability to 'get' good-looking men as if fishing them out of the television. Aside from headaches as her brain struggles to keep the lid on her buried incest childhood by cloaking it in all sorts of nautical imagery and oceanic sound effects, she's perfect. Maybe she's mad as a hatter, and has a weird thing for good-looking men on TV, as if they can see her from the screen, and are propositioning her. Maybe she keeps talking about her lost-at-sea captain father as some kind of omnipotent hero despite her more grounded sister who assures her kids he was a monster. But she's not 'victim' crazy, not a cringing trauma victim or a twitchy mess. She's crazy in a way that encompass sanity within itself. When a bubbly blonde actress (Roberta Collins) at the bar bemoans not being liberated, which is now a requirement for TV she glances over at Molly in her patchwork denim and declares she could be in commercials: "You look liberated." The older barmaid Doris (Peggy Furey) adds that "Molly is a saint, a goddamned American saint." Later when her nervous welfare-collecting sister Cathy (Vanessa Brown) shows up to try and convince them of the truth, "you think she's just about perfect," she says to Long John. "Yeah," he snaps back, "why not?"

We agree, thanks to Millie Perkins' dynamic, confident, warm portrayal we love her as much as the staff and her nephews do. Anything she does is all right with us. She's a goddamned American saint.

That's what makes it so tragic. Molly is a liberated saint, yes, but she has no grasp on reality, and it's not the social world's fault, it's the fault of the family dynamic that would let her vile father rule the roost in such a horrifying way (we never see if she has a mother). It's a mix of latent, incest trauma-induced schizophrenia, wherein she sees people on TV talking to her, and her childhood is--understandably--warped and blurred in a salty sea spray of nautical mythology, punctuated by deeply unsettling visions. She has a habit of being drawn to people on it or connected with television, only to then kill them or is she merely fantasizing. She presumes the latter but lately, who knows. If she hears someone is dead she announces she won't believe "if it's true or not until it's on television." As if TV isn't lying to her constantly, the men on it leering out at her, calling her forward. Her dichotomy seems to be a relaxed ease in the anonymous oceanic of the bar, and the bed of salty pirate Long John, a grizzled old reprobate who accepts Molly as she is, no strings. ("Molly is the captain of her own ship.") The bed seems to be in the bar itself, and as such it becomes a very weird uniquely 70s cool spot, with panelling and aquariums and mermaid and nautical bric-a-brac, including those painted mirrored wall tiles that are often associated with orange shag and faux rock walls.

|

| "Her father was a god; they cut off his balls and threw them into the sea." |

The ocean plays a huge part, though the film never gets out on a boat, we see the ocean outside the window, and hear it deep in the sound mix, the town where they live seems largely deserted, so shops like Jack Dracula's tattoo parlor loom with an almost Lemora-style surrealism. The flashbacks are all given a surreal, sometimes darkly comic, patina, with comically distorted or ocean sound effects as if her brain is working overtime to contextualize the most primal and odious of endured horrors in terms of oceanic myth. The sea itself becomes her father, a timeless chthonic wellspring, an ultimate signifier connecting this film to everything from Treasure Island (hence the name Long John) to Moby Dick (the local tattoo artist's long tattooed face evokes Queequeg). The soundtrack is a brilliant melange of background sound (the ocean's waves are never out of earshot) and ironic electronic counterpoint: when the melody of a sea shanty she's half-singing while going in the bathroom, the two football players tied up, is suddenly picked up and finished by the ominous soundtrack as she comes back with a razor, its the kind of darkly comic interjection that would make John Williams probably shit himself with fear ("do you shave with straight razors, or is this all going to be agonizingly slow?"). When Molly learns of Venus, born in the sea, according to one of her pursuing men, ex-movie star Billy Batt (Rick Jason - above) she says, with child-like sincerity, "You're lying to me." It's a brilliant line, she could be kidding in a cocktail party way, or it could be an indication her concepts of reality, myth and TV are hopelessly blurred together. And in fact, it's both and why not? This is the age of liberation and free-thinking - where the structure of reality is far looser than it used to be. A latent schizophrenic barmaid isn't even judged for her violent bedroom actions, but loved and accepted by those around her, neither in spite of or because of her castrative tendencies.

And as in any ocean, there are storms: when all other boundaries fail her, her oceanic visions become terrifying pictures of being tied to the mast of a free-floating raft, surrounded by dismembered male bodies, as if remembering some primal prehistoric siren past (only without a hypnotist Chester Morris pulling the strings). The split between her castrating angel of death, turned on by sadism and dismemberment, both as projection revenge against her father and tricks maybe taught by him (we never really know - or hear his voice), and her sweet aunt / fun carefree cool barmaid type is as vivid as the difference between TV and reality. "Let's get lost at sea, Molly m'lass" is what we learn her father used to say, "and we got lost at sea so many... many times." The ocean surge mirroring the rise and fall of the bedsprings - its base horror itself part Greek myth (Elektra) and part Sumerian or druid sacrificial cult, the young boy castrated and his loins thrown into the sea to ensure a good harvest of fish (or wheat if on the fields).

Long John seems somehow to be spared, to share a bed. Maybe due to his easygoing attitude, age, that he's not on TV, and his ability to be contextualized into her nautical miasma (he's a "pirate"). He certainly never reigns in her sexual adventurousness or belittles or infantilizes her. He says he's too old and experienced to get jealous, he says, and we believe him. But you know he loves her, and is willing to take her at face value, as much as he can. He's no fool though, and when he asks her when she lost her virginity and she can't remember that far back, starts stalling and getting a headache he realizes immediately and to some horror the truth; the script and film don't need to underline the moment. He gets it, and his whole demeanor changes, and so we get it too, without ever needing it heard aloud. It's a brilliantly modulated bit of acting by them both. These are smart, interesting people, with unique bonds.

THE MYSTIC ORACLE:

One thing that most horror movies, or any movies, lack is the presence of TVs. They're hard to film due to streaking, so often they're just left off, but it really spells the difference between a believable reality and this kind of utopia where people just sit around in empty kitchens waiting for their cue. Here, though we can clearly see the TV image is superimposed to avoid telltale streaking, that actually works to give the images an extra eerie frisson. TV is a constant extrasensory, imposed presence: in her childhood memories a very creepy black-and-white clown makes all sorts of weird swimming gestures towards her, beckoning to her/us in a way that's genuinely unsettling. Watching, I had the distinct feeling some terrifying being from my own childhood dreams had found me and was beckoning me from across time and media. Other genius moments tap into LSD experiences (every hippy's schizophrenic sampler), as figures talking to the camera on TV seem to be addressing us/Molly directly. No sooner has she seduced Alexander McPeak (Stafford Morgan) after seeing him in a shaving commercial ("Don't bruise the lady,") she's receiving bizarre directives directly from his TV commercials, telling her where and how to take that razor across his jugular vein.

|

| "He's stark naked! Everywhere... looking at me!" |

Trying to find out how this amazing film could be made, could emerge so fully formed from the frothy foam of independent horror cinema, we need to look at the credits, for both Thom and director Climber have unique outlooks on feminine strength indicated by their other films. Thom's body of work shows a latent queer eye for strong young beautiful men, fully-formed (non-objectified) females, and his films often feature a strong, domineering mother figure (as in his scripts for New World: Bloody Mama and Wild in the Streets, Angel Angel Down We Go) He's the exploitation market's Tennessee Williams, tapping into the same vein of Apollonian beauty reaching like Icarus, for the sun, swallowed up by the maternal chthonic of the devouring mother. In fact, Witch's conspicuous absence of a human mother figure allows for the sea itself (ever-present, either in the sound mix or the frame) to step into the role (and nobody does it better), its warm, forgiving maternal tide like a ceaseless flow of half-dissolved titan testes, and scuttling crustacean claws (by Gillette). Keenly aware of its archetypal resonance (yet avoiding literality), The Witch who Came from the Sea would make a great mythopoetic subtextual gender/death-swapped double bill with Suddenly Last Summer, with Molly's sister as the Mercedes McCambridge (there's even a bit of the same speaking pattern), Long John the equivalent to Liz Taylor, and Molly herself as the dead Sebastian and hid cannibal bird beach boys, soft-swirled into one many-armed/headed deity.

Promise me you'll think about it? Constantly?

Director Matt Climber is the other major "ally" that helps make Witch so redolent, as his love of strong female characters very much in evidence. Basically the real-life inspiration for Marc Maron's character in GLOW (there's even a passing resemblance between GLOW star Alison Brie and Perkins), between that and his 1983 Conan-ish film Hundra, about a wandering blonde Amazon warrior who teaches an oppressed group of women how to rise up and smite their bullying men, it's clear Climber's got a unique appreciation for very strong, assertive, capable women. He also loves Molly as much as Thom, Perkins, and the actors and their characters in the film do. I love her too. I love this film.

I love the weird, uncommented on details I haven't even mentioned: the way Molly and Long John sleep downstairs in the bar, that it converts to a bedroom, one with a cigarette machine by the stairs (who doesn't want a cigarette machine in their bedroom?). We never quite figure out how that works, if the bed pulls down or something, but it doesn't matter. I love the way all the scenes have that strange 70s mirror tiling and gorgeous deep wood decor, as if they're all the same place. Things that bear examination aren't addressed, but that's to its credit. Not since Antonioni's Red Desert (1964) have commercial and private space been so subtly blurred. I love the way Climber uses the cinematic time image as a reflection of Molly's dysfunction (just a single cut could bridge years, hours or seconds, how she can seemingly commit murders in the space between taking a drink and putting the glass down). I love the seamless way she goes from being playfully sexual to totally deranged, and the subtle pitch-shifts in her voice as her inner siren emerges, voice getting low and draggy like a riptide. It's all so very fierce. I've already visited its shores three times since that fateful post-Climax night! Won't you sail away on it too? It's on Prime so there's no excuse to shun it. Not anymore. It may not put you in that tropical island mood but it will give you that old-time religion.... older than Aphrodite, older than Innana, Ishtar, Asherah and Astarte! Old enough to sail the sea without a rudder, knowing your raft is safe--at last-- in your mother's foamy talons... Adieu, Belladonna, the Lady of the Rocks. Good night. At the count of three... a wake.

Great to be able to read your thoughts on this film Erich - it's long been one of my absolute favourites. So underrated, so misunderstood and weirdly marketed... and yet, it's one that I'm reluctant to shout about or tell people they should watch (perhaps for obvious reasons).

ReplyDeleteIn a way, I can't help seeing it as a kind of dark twin to Curtis Harrington's 'Night Tide' - such a similar vibe, so much shared imagery (and the same shooting locations, pretty much), but with the nascent boho magic(k) of the emerging early '60s counter-culture replaced with the harrowing, booze & pill-blurred trauma of its aftermath...

Thanks for your wisdom Ben, I thought about tying in NIght Tide but didn't want to tap into Dennis Hopper's aching sailor loneliness. It's so much more his story than hers and his melancholy hangs heavy. Still I'm working on a cinemarchetype list for 'Elementals' and she'll be in it, in the water section, of course, with Esther Williams

ReplyDelete