Leave it to Europe to deliver on the promise of HD cameras and non-union expressionist German handwerkers, taking the time to bring old masters' lighting and composition to even their low budget fantasy. Here are three fairly interesting, more or less family-friendly but dark, fairy tale-style forays into deep Jungian crypto-horror from the Emerald Isle, Germany and Italy. The accents might not always be there (they sometimes seem to be doing 'American') but the lighting runs from good to decent. These aren't your average DIY SOHDV mile-wide misses, they're legit little minor key gems looking for a rocky outcrop in the middle of the YA fantasy fiction and horror waterfall to nestle in, there to patiently wait for the right mopey young person--perhaps the type to read Bronte or Keats while perched on a fractal-patterned tapestry spread over the mossy rocks--to catch the secret glint of in the corner of their glasses.

That they are all findable in the rocky maze of Prime is a blessing. Normally we'd be able to see these only at a 'Fantastic Film'-style festival, where sneaking out after ten minutes would be, well, you'd hate to do it since you know the filmmaker and cast are probably in the row behind you and you're the only non-crew/cast member there, and really, it's not them it's you, etc. One of the reasons I stopped submitting my own work at festivals was to avoid this very thing. Just know this: the genesis of this post began after my surprise at the loveliness of The Forbidden Girl's cinematography. The other two films listed were the only ones I could watch to the end. I've started, stopped and flicked around on, dozens of similar titles on Prime just to get to these three (I was hoping for at least five); so bask in your moment if one of these lost kittens are yours! The rest of you, bring your grains of salt, your huddled sage-and-sandalwood candles yearning to be lit... and press play.

NEVERLAKE

(2013) Dir. Riccardo Paoletti

**1/2 / Amazon Image - B+

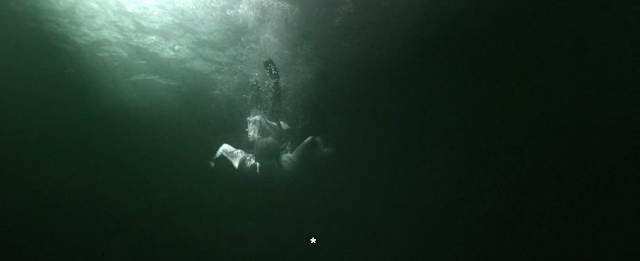

You'd be forgiven thinking this a UK production --the actors are all Brits, Welsh, Irish. But it's an German-Italian joint and--despite the near constant UK-style dinginess of the skies--filmed in Italy! Independent-minded Jenny (Daisy Keeping) is spending a summer with her absentee archaeologist father near an ancient Etruscan lake, from which he's been exhuming ancient fetish totems. In ancient times, these small carved stones used to be tossed into the lake as sacrifices to the spirits. He's been taking them out, but also throwing other stones in, for some reason. Mostly he's gone, researchin' - so she's stuck at home, semi-bullied by a dimly evil au pair named Olga (Joy Tanner) or reading Shelley down by said mysterious lake, a practice that soon draws her an audience of handicapped children with the kind of pale ghostly faces that raise all sorts of red flags for any normal person. But Goth-crazed Jenny gathers them up like a babysitter den mother. Uh oh....

In addition to the whole Etruscan statuary element (shoehorned into the narrative with the finesse of a frostbitten safecracker), there's passages from Shakespeare (guess which play? Hint: one of the pale urchins is a brooding older boy with Edward Cullen facial planes).

Enriched with mythic meaning, often to the point of anything else, writer-director Martin Gooch clearly knows his Maria-Louise von Franz, and ably uncorks the genie of Jungian archetypal psychology which brings glowing Meaning to everything, as Jenny takes on the job of recovering the statues stolen by dad and throwing them back into the lake, and in the process finding a mysterious doorway hidden behind a log pile leading to a secret chamber!

What new mystery lies beyond!?

In addition to the whole Etruscan statuary element (shoehorned into the narrative with the finesse of a frostbitten safecracker), there's passages from Shakespeare (guess which play? Hint: one of the pale urchins is a brooding older boy with Edward Cullen facial planes).

Enriched with mythic meaning, often to the point of anything else, writer-director Martin Gooch clearly knows his Maria-Louise von Franz, and ably uncorks the genie of Jungian archetypal psychology which brings glowing Meaning to everything, as Jenny takes on the job of recovering the statues stolen by dad and throwing them back into the lake, and in the process finding a mysterious doorway hidden behind a log pile leading to a secret chamber!

What new mystery lies beyond!?

Occasional missteps: the Medusa hair effect of one of the water nymphswould have been much more effective if they moved languid like flowing seaweed (as Val Lewton would have done it) and the Etruscan statue tossing thing is kind of bum rushed past us, as if the writers sincerely hope we won't notice the stank of an upcoming social studies quiz creeping in like a dad trying to interest his children in state history during a long car ride.

Either way it's fairly engrossing, makes interesting use of pans and dissolves (as in the above, where a painting of robed figures seems to imprint itself on the twilit lake), and features a pretty riveting climax with lots of drug use (I can't say more). It's great to see movies where the new girl in town isn't saddled with cumbersome school alienation tropes or romantic sogginess and has just the right level of Elektra complex. Jenny might get pissed when dad keeps ignoring her, but she finds things to do other than pine for some dead boy, and if the climax doesn't quite make as much sense as the filmmakers seem to think, at least they have the courage of their convictions, and one ends up feeling compassion for most everyone of the characters, save one....

THE GATEHOUSE

(2016) Written and directed by Martin Gooch

**1/2 / Amazon Image - A-

Though on the surface it's yet another modernized fairy tale where the intrepid young daughter of a slightly-overwhelmed, gruff but lovable widower (Simeon Willis) recovers mysterious stones in order to defeat a horned monster of the ancient woods, there's a lot more going on here than just the usual trite nonsense we'd get in an American movie following the same beats (the dad doesn't mope around watching videos of his dead wife, and when he flashes back, it's of them getting drunk in a canoe together!) Their ghost Mom appears to both father and daughter, warning them of coming danger, so dad can't just blow it all off, like usual. By day, dad occasionally raises his voice and flies into overwhelmed fits while trying to follow the strange clues ghost mom leaves and fix breakfast for his super-inquisitive daughter Eternity (Scarlett Rayner) --- but the pair can also share uniquely nice moments together, like treasure hunts and evenings outside on lawn chairs looking up at the stars ("if I ever get to ill or too old to have a beer under the stars," he tells Eternity, "I want you to put me in a little boat, and set fire to it...") Right on, Willis.

Fans of Irish horror will recognize the oft-used fairie lore moral of 'if you take things from out of the woods you had best return them', which was also underwriting another Irish horror, 2015's The Hallow. Here, Gooch wisely keeps the focus on the brilliantly precocious and alert Eternity as she mucks about digging holes, looking for treasure; she may not be quite aware of the forces she's messing with (as when she hacks into a power cable in the front yard) but she's able to meet the creepy gaze of the enigmatic shotgun-toting neighbor (Linel Aft) without so much as an imperceptible shiver.

But what really sells it is the well-tempered rapport between Eternity--her super long straight hair picking up impressions like a 10 year-old Maria Orsic--and her only-mildly overwhelmed and disheveled, vaguely taller-Ricky-Gervais-ish dad--they seem like both opposites and clearly related--with him gruffly giving her pointers for sticking up for herself against bullies, and gradually realizing he'll be totally overwhelmed on his own search for answers unless he brings her along. Once his investigation into the magic stones leads him to the truth, it's nice that he has no problem totally believing his daughter. How often do we see a dad offering anything but sleepy irritation or pasteurized reassurance when his daughter starts screaming about something being under the bed? Not this dad! He gets down on his knees to look, and he's scared, and so is the musical score! This is a world where bumps in the night aren't just delusions; we've crossed over into fairy tale land but without ever being quite aware there was a door to go through.

There's an ecological message underlying things but it never gets heavy-handed. In this case the CGI is better modulated than in most such low budget films: branches reach out and victims of a woodland "Green Man" style horned guardian of the forest captures those traveling through the woods and meshes them into the roots of trees - a pretty scary, well-done effect. There are also some terrifying parental dreams dad has, as when he cuts off his daughter's fingers because she won't put down her iPad! The fairy tale intensity of this all works to keep things uneasy and may scare children into realizing the emotional fragility of adults who become shut out of their kids' lives due to cell phones. People die in this film, in true fairy tale grimness; even an innocent lady cop who spends the day wandering around the woods, evoking a mix of Winona Earp's sister's cop girlfriend Nicole, and Amy Pond in her cop costume in the first Matt Smith episode of Dr. Who. (2)

Fans of Irish horror will recognize the oft-used fairie lore moral of 'if you take things from out of the woods you had best return them', which was also underwriting another Irish horror, 2015's The Hallow. Here, Gooch wisely keeps the focus on the brilliantly precocious and alert Eternity as she mucks about digging holes, looking for treasure; she may not be quite aware of the forces she's messing with (as when she hacks into a power cable in the front yard) but she's able to meet the creepy gaze of the enigmatic shotgun-toting neighbor (Linel Aft) without so much as an imperceptible shiver.

But what really sells it is the well-tempered rapport between Eternity--her super long straight hair picking up impressions like a 10 year-old Maria Orsic--and her only-mildly overwhelmed and disheveled, vaguely taller-Ricky-Gervais-ish dad--they seem like both opposites and clearly related--with him gruffly giving her pointers for sticking up for herself against bullies, and gradually realizing he'll be totally overwhelmed on his own search for answers unless he brings her along. Once his investigation into the magic stones leads him to the truth, it's nice that he has no problem totally believing his daughter. How often do we see a dad offering anything but sleepy irritation or pasteurized reassurance when his daughter starts screaming about something being under the bed? Not this dad! He gets down on his knees to look, and he's scared, and so is the musical score! This is a world where bumps in the night aren't just delusions; we've crossed over into fairy tale land but without ever being quite aware there was a door to go through.

There's an ecological message underlying things but it never gets heavy-handed. In this case the CGI is better modulated than in most such low budget films: branches reach out and victims of a woodland "Green Man" style horned guardian of the forest captures those traveling through the woods and meshes them into the roots of trees - a pretty scary, well-done effect. There are also some terrifying parental dreams dad has, as when he cuts off his daughter's fingers because she won't put down her iPad! The fairy tale intensity of this all works to keep things uneasy and may scare children into realizing the emotional fragility of adults who become shut out of their kids' lives due to cell phones. People die in this film, in true fairy tale grimness; even an innocent lady cop who spends the day wandering around the woods, evoking a mix of Winona Earp's sister's cop girlfriend Nicole, and Amy Pond in her cop costume in the first Matt Smith episode of Dr. Who. (2)

My favorite bit is the third act, when both mom of the babysitter and dad finally believe the kids and they all go on an armed expedition into the woods to find the horned god, and there's even a Goth psychic (Anda Berzina) friend of the sitter (Zara Tomkinson) who drifts over to read tarot cards. As with Neverlake, strange country houses turn out to have hidden rooms deep within secret chambers accessible only from trap doors hidden in the base of closets or woodpiles. By the end one has grown quite fond of all the characters (save one) and we wouldn't be averse to a nice sequel. Like Neverlake it has the air of a YA fantasy novel, and there are virtually no boys at all, just a few adult males pointing dad towards the horned truth, and the strange Mr. Sykes for counterpoint.

PS: For a similar film, more adult, check out another big favorite discovery of recent years, Michael Almereyda's The Eternal (1998)

PS: For a similar film, more adult, check out another big favorite discovery of recent years, Michael Almereyda's The Eternal (1998)

--

THE FORBIDDEN GIRL

(2013) Dir Til Hastreiter

*** / Amazon Image - A+

What a difference a talented ambitious cinematographer makes! Merely OK films become great, or at least worth a glimpse. 99% of the unknown stuff floating on Prime is shot on HD video, in this case it's the staggeringly pretty looking (especially for such a dismal and unfair imdb rating, a staunchly undeserved 3.4) movie that lets you know just how good digital film can look with the right painterly craftspeople at the helm. My observation through relentless slogging is that such brilliance is almost always the result of an Eastern European craftsman, with the artsy eye to deliver beauty that, like in Ivan Brlakov's stunning work The Bride, transcends the film it services. In this case, it's Hungary's Tamás Keményffy, who brings a golden dusk sharpness to German-Dutch production, The Forbidden Girl, a (filmed in English); a tale of Jungian high weirdness I stumbled on via Prime when I was drawn to the cover art.

The result? It might be my favorite random discovery since Bitches' Sabbath (i.e. Witching and Bitching). It's a little rough around the narrative edges, but it's a nicely acted and sometimes well-written tale of the anointed (American) son whose mysterious (German) dream lover may well be either a witch or imprisoned by one. Toby McLift (Peter Gaidot) is sent to a mental hospital after his looney-tunes Baptist preacher dad murders his girlfriend; he's hired as a tutor in residence at an ancient, crumbling mansion that just happens to hold his true love chimera girlfriend. But if he thinks he's going to have an easy time teaching her though or rekindling their passion, he's wrong. For one thing, she doesn't even remember him! For two, her guardian is a towering, supernatural, controlling Germanic watchdog played Klaus Tange (Strange Color of Your Body's Tears), who skulks ever within hearing range.

Hamburg-born, Strassberg-trained actress Jytte-Merle Böhrnsen is alive and wild as this forbidden girl Laura, a classic Jungian anima figure, whose kept in a tower, away from the eyes of strangers, though why her guardians should want a doe-eyed lovestruck mental case like British-born dreamboat Peter Gadiot up there as a tutor is anyone's guess, unless it's because he bears 'the mark' that will open doors to Hell. That's not really a spoiler if you've seen enough of these kinds of films. But what's unusual is the great use of the crumbling mansion as a sprawling set that puts the Overlook and Hill House both to shame. Scenes take place by a leaf-filled crumbling half-full indoor pool, for example, or along dark twisted hallways, and into small ditches around the property. We get a real feel of the architecture through the ever-prowling camera.

The result? It might be my favorite random discovery since Bitches' Sabbath (i.e. Witching and Bitching). It's a little rough around the narrative edges, but it's a nicely acted and sometimes well-written tale of the anointed (American) son whose mysterious (German) dream lover may well be either a witch or imprisoned by one. Toby McLift (Peter Gaidot) is sent to a mental hospital after his looney-tunes Baptist preacher dad murders his girlfriend; he's hired as a tutor in residence at an ancient, crumbling mansion that just happens to hold his true love chimera girlfriend. But if he thinks he's going to have an easy time teaching her though or rekindling their passion, he's wrong. For one thing, she doesn't even remember him! For two, her guardian is a towering, supernatural, controlling Germanic watchdog played Klaus Tange (Strange Color of Your Body's Tears), who skulks ever within hearing range.

Hamburg-born, Strassberg-trained actress Jytte-Merle Böhrnsen is alive and wild as this forbidden girl Laura, a classic Jungian anima figure, whose kept in a tower, away from the eyes of strangers, though why her guardians should want a doe-eyed lovestruck mental case like British-born dreamboat Peter Gadiot up there as a tutor is anyone's guess, unless it's because he bears 'the mark' that will open doors to Hell. That's not really a spoiler if you've seen enough of these kinds of films. But what's unusual is the great use of the crumbling mansion as a sprawling set that puts the Overlook and Hill House both to shame. Scenes take place by a leaf-filled crumbling half-full indoor pool, for example, or along dark twisted hallways, and into small ditches around the property. We get a real feel of the architecture through the ever-prowling camera.

And in bed in a different room, withered and dying though slowly growing mysteriously younger with Gaidot's presence (ala Hasu, or I Vampiri), waits is the enigmatic witch Lady Wallace (Jeanette Hain). You won't need a copy of Campbell's Hero of a Thousand Faces to figure out what's really going on (or why even a tiny amount of sunlight--as when a shade accidentally flips up--can set fire to ancient books and generally wipe these witches out. As the light creates a weird camera obscura image on the side of what looks like a transparency projector, we're forced to admit that, unconvincing as it is, it's all way prettier, better, and more genuinely surreal than Lynch's Twin Peaks: The Return.

But these kinds of dark fairy tales are never about either story of beauty - they're about the journey, these are the equivalent of the tales children love hearing over and over, because the story rings deep into the fabric of our unconscious tapestry, shaping the way we view the world and giving our dreams the narrative structure our unconscious is often not enough of a dramatist to provide. Here we get the same balmy 'living all ages of life at once' thing we get in Valerie and her Week of Wonders, Lemora, and even Muhlholland Dr. to a weirder degree. It's not 'better' than those films, but it is certainly lovely to look at, with deep blacks and rich moody colors that evoke the saturated interiors of Next of Kin's old folks home, or the autumnal leaf-bedecked scenery of José Ramón Larraz films like Symptoms and Vampyres. The CGI is bad, but you can't have everything!

But these kinds of dark fairy tales are never about either story of beauty - they're about the journey, these are the equivalent of the tales children love hearing over and over, because the story rings deep into the fabric of our unconscious tapestry, shaping the way we view the world and giving our dreams the narrative structure our unconscious is often not enough of a dramatist to provide. Here we get the same balmy 'living all ages of life at once' thing we get in Valerie and her Week of Wonders, Lemora, and even Muhlholland Dr. to a weirder degree. It's not 'better' than those films, but it is certainly lovely to look at, with deep blacks and rich moody colors that evoke the saturated interiors of Next of Kin's old folks home, or the autumnal leaf-bedecked scenery of José Ramón Larraz films like Symptoms and Vampyres. The CGI is bad, but you can't have everything!

One of the story's many strengths is the total absence of a distinct black/white dichotomy. We empathize with the romantic yearning and sense of irrecoverably lost time in the sad eyes of the older pair of lovers and can't help but wonder whether the real villain is actually Toby in his blind determination to rescue Laura whether she wants to go or not.

|

| Jeanette Hain |

All together, taken as a triptych, we get in these three films what can happen when imaginative low budget filmmakers let loose with enough of a European sensibility that their work isn't stepped on by a lot of second-guessing producers. We learn that children in fantasy movies needn't be doe-eyed drips or crass morons, and parents needn't be saints or sex offenders with no room in between. Childhood fairy tale wonderment and adult sexuality (portions of Forbidden Girl get pretty racy) go hand-in-hand. Wether it's delivering stolen ritualistic stones back into the hands of woodland spirits or shagging 300 year-old witches during arcane rituals, these tales take us home, to the real home. When told with the feeling of real danger, alive with real magic, the secret doors hidden in our gatehouses open, and along with the demons comes everything we ever thought was lost, all those traumas too rough to recall in the same decade they happened, all those intense in-love moments that were so great they left you feeling hollow and lost for years after they ended, vainly trying to get back to the garden until, by the time you got there, that garden was a wasteland, plants all dried and dead... You took too long to get there with the watering can and now aren't even the same person that left. But maybe the golden intense love you lost is still waiting, inside the innermost secret chamber of your dream castle.

Stop looking for the key and there it is.

NOTES:

2. Surprise! If you get those two references, thou art a geek