"Masculinity must fight off effeminacy day by day.

Woman and nature stand ever ready to reduce the male to boy and infant."

-Camille Paglia (proud Italian-American)

"Son? I wish I had one! He's a bum!"

--Mama Mantana (Scarface)

You can argue that gangster cinema began at Warners with Cagney and Robinson, but a few pre-code masterworks aside, the gangster never hit his grandiose peak until it became a distinctly Italian-American saga, directed by an Italian-American with maximum tactility. Robert Evans knew this, and so insisted on Coppola for The Godfather (1972). An Italian director for an Italian story, this according to Evans' Kid Stays in the Picture. Defamatory? Maybe. But the Italian-American Anti-Defamation league was founded by one of the heads of the five families, Joe Colombo, as a front for mob activity, so who can you truss? Me, 'ass who.

And so you need an Italian-American director, or an Italian straight-up, one who is going to ideally bring in a sense of Italian flair and artistry, i.e. the Scorsese 'boy pack' forward momentum, the Coppola darkness, and the De Palma operatics. And just the word "opera" should make you think of Argento, an Italian, straight-up, whose films have such elaborate beauty, brutal violence and strange rhythms that he even called on of his films Opera (check out my 10/2009 companion to this piece, "Nightmare Drive-In Logic, Italian-style); they transform the work of everyone who sees them... whatever that work may be. Mine included

And so you need an Italian-American director, or an Italian straight-up, one who is going to ideally bring in a sense of Italian flair and artistry, i.e. the Scorsese 'boy pack' forward momentum, the Coppola darkness, and the De Palma operatics. And just the word "opera" should make you think of Argento, an Italian, straight-up, whose films have such elaborate beauty, brutal violence and strange rhythms that he even called on of his films Opera (check out my 10/2009 companion to this piece, "Nightmare Drive-In Logic, Italian-style); they transform the work of everyone who sees them... whatever that work may be. Mine included

Italian-Americans and Italian-Italians don't all love opera but it's emblematic of their artistic genes, along with the poetry of Dante, the art of Botticelli, Da Vinci, Michelangelo, and the masochism of Catholicism (each centurion lash upon the wrecked torso of Christ fantasized about in excruciating detail). All this and more pumps, drives, twists the flagellant Italian heart, consumed by "original sin," which stretches its exposed raw nerve beating-heart history back through Roman orgies, gladiators, court intrigues, brutal inquisitions, the plague, Il Duce. Thus the murders in Argento and De Palma and Scorsese and Coppola sing like operas of the damned, in which every emotion is heightened, and played out in full, wringing every last drop of blood and pain. They present characters who are adults, who sometimes joke around with each other, but never about business, and who keep their wives and mother out of it --wayyy to the side, and do not let the apron string hydras devour them the way they devour our 'sensitive' liberal guys. They're real men, unless they're really women, and when violence occurs to or through them it's always painful, always transmitted across the screen with time for the victim to scream, or scrawl a note on the tile steam, or be confronted by his own pulled-out small intestine, to protest, cringe, plead, try and crawl away and--recognizing the end, to screw forth enough macho courage to stare one last time into the eyes of their killer and shout "Fack Yew!"

In these films, death may be cinematic and beautiful, but it also hurts. No one dies easy; no one just gets shot or strangled and dies in a second. Characters get time--even if just a second--to register the horror of realizing their whole life is about to end, suddenly and with no good reason, and so much left undone. They see death coming, and if they live long enough to kill in kind they make sure their opponents get the same luxury. There's a feeling in this operatic Italian schemata of what might really involved with killing people. In normal gangster films people just get shot, Blammo! But being true to Italian operatic rhythms means one needs time to die, a whole scene for one lengthy tortured aria while Ennio Morricone strings play a semi-mocking eulogy overhead and you look at your killer with a slow turn from pleading to fear to anger and oaths, to resignation and then downwards or up into the infinite abyss, or onto some busy Rome street while passers-by hustle past you on your way to work and it's not until you fall face down and the blood pools in the middle of the sidewalk do they finally stop and scream. Death isn't the scariest thing in De Palma or Argento films, it's the loneliness of it that hurts the worst.

In these films, death may be cinematic and beautiful, but it also hurts. No one dies easy; no one just gets shot or strangled and dies in a second. Characters get time--even if just a second--to register the horror of realizing their whole life is about to end, suddenly and with no good reason, and so much left undone. They see death coming, and if they live long enough to kill in kind they make sure their opponents get the same luxury. There's a feeling in this operatic Italian schemata of what might really involved with killing people. In normal gangster films people just get shot, Blammo! But being true to Italian operatic rhythms means one needs time to die, a whole scene for one lengthy tortured aria while Ennio Morricone strings play a semi-mocking eulogy overhead and you look at your killer with a slow turn from pleading to fear to anger and oaths, to resignation and then downwards or up into the infinite abyss, or onto some busy Rome street while passers-by hustle past you on your way to work and it's not until you fall face down and the blood pools in the middle of the sidewalk do they finally stop and scream. Death isn't the scariest thing in De Palma or Argento films, it's the loneliness of it that hurts the worst.

Thus it makes sense that De Palma has no real interest in capturing the Cuban culture of Miami, filling the score instead with the boss Italian synths of Giorgio Moroder, and the gaudy pre-fab architectures of the Floridan disco. Hawks' 1932 Scarface bounced around with merry good-cheer and a mock-Italian comedy-team rhythm that made a stunning counterpoint to the violence; Paul Muni showed that thing we all love about our one Italian-American friend: their positive life force--always on, never wavering, how-- even when they're breaking your thumbs for not paying your debts-- they can joke around and make you feel like a regular guy and ask you how's your mother and seem to mean it. And if you dated one then you know how nurturing their women are, cradling your head when you throw up, and only crying and freaking out when they realize you are never going to stop drinking long enough to be much of a take-home-to-the-parents-style boyfriend.

Scarface's ice princess blonde Elivra, played as a bundle of nerves snaking themselves through sheer brass will into the shape of a svelte cat-eyed bombshell (by Michelle Pfeiffer in her big breakthrough) is the opposite of the gaudy Italian persona. She's so trapped in the narcissist WASP mirror she can't wait to snort the lines off it, all the better to see herself with. But if you can get her to laugh, a woman like that? Ah Manolo, she break her septum for you. Plus, she's forbidden. That's the boss's lady, ogay? But Tony values only that which he cannot have because he's too dumb to know in advance that attaining it will bring him no satisfaction. when he gets all he wants even then he has to look closer to home, towards the ultimate taboo of incest. He falls for his sister the first time he sees her as a young woman. That he's been in jail for five years in Cuba excuses it somewhat at first (the way it didn't in the original) but then he makes no effort to rein in his incestuous impulse. He can't even admit he feels it, so makes no attempt to question the violence of his jealousy.

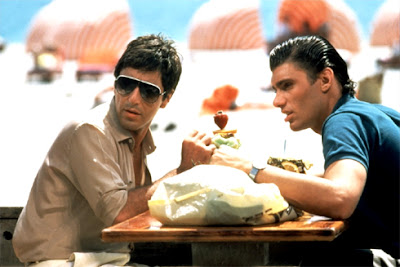

As Tony, Pacino is filmed first in long shots, his musky tan face paint dripping off when he's hot--which is all the time--or being bathed in Angel's watery blood with a gun to his head, the blood and brown make-up swirling together to form a muddy rust. In the early scenes, when he's bluffing his way up into Lopez's good graces, he seems to fold into himself like a sullen teenager. All terrible bangs and loud shirts, short frame and hairy arms, he's an illiterate peasant trying to cover up his clueless innocence with tough talk and bravado and big cigars (see below). De Palma's camera doesn't circle at this early stage, but rather observes him from on high, in a kind aloof regard. As Tony increases in stature and drive, De Palma's camera moves in for close-ups and lower angle shots, subliminally accentuating both his rise in stature and the disorientating effect of chronic cocaine abuse. Pacino's performance imperceptibly mutates to accompany this slow trend, oscillating at first back and forth between tough guy killer and loyal clown, gradually losing the clown aspect along the way and replacing it with self-absorbed money-obsessed paranoia, as if Elvira's glum narcissism is seeping into him through prolonged proximity.

Scarface's ice princess blonde Elivra, played as a bundle of nerves snaking themselves through sheer brass will into the shape of a svelte cat-eyed bombshell (by Michelle Pfeiffer in her big breakthrough) is the opposite of the gaudy Italian persona. She's so trapped in the narcissist WASP mirror she can't wait to snort the lines off it, all the better to see herself with. But if you can get her to laugh, a woman like that? Ah Manolo, she break her septum for you. Plus, she's forbidden. That's the boss's lady, ogay? But Tony values only that which he cannot have because he's too dumb to know in advance that attaining it will bring him no satisfaction. when he gets all he wants even then he has to look closer to home, towards the ultimate taboo of incest. He falls for his sister the first time he sees her as a young woman. That he's been in jail for five years in Cuba excuses it somewhat at first (the way it didn't in the original) but then he makes no effort to rein in his incestuous impulse. He can't even admit he feels it, so makes no attempt to question the violence of his jealousy.

As Tony, Pacino is filmed first in long shots, his musky tan face paint dripping off when he's hot--which is all the time--or being bathed in Angel's watery blood with a gun to his head, the blood and brown make-up swirling together to form a muddy rust. In the early scenes, when he's bluffing his way up into Lopez's good graces, he seems to fold into himself like a sullen teenager. All terrible bangs and loud shirts, short frame and hairy arms, he's an illiterate peasant trying to cover up his clueless innocence with tough talk and bravado and big cigars (see below). De Palma's camera doesn't circle at this early stage, but rather observes him from on high, in a kind aloof regard. As Tony increases in stature and drive, De Palma's camera moves in for close-ups and lower angle shots, subliminally accentuating both his rise in stature and the disorientating effect of chronic cocaine abuse. Pacino's performance imperceptibly mutates to accompany this slow trend, oscillating at first back and forth between tough guy killer and loyal clown, gradually losing the clown aspect along the way and replacing it with self-absorbed money-obsessed paranoia, as if Elvira's glum narcissism is seeping into him through prolonged proximity.

We learn from books like The Devil's Playground that De Palma 'knew something about gogaine' and if you look at this movie and the bloated satire of Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) and The Untouchables (1987), as a trilogy, you get a saga of desire, loss, and how empires might be built on the underbelly of America's endless thirst for getting fucked up vs. the futile attempts to inflict the morals of senator's wives onto the common people while their rarely-home husbands get rich from under-the-table kickbacks, the money increasing relative to the intensity of government crackdown. The importance of not getting high on one's supply is understood so deeply you can feel De Palma's good judgment slipping away as the film goes on, for he too, clearly, is breaking that rule. I don't think that's libelous to say - it's not like it wasn't the style of the time. I'm not judging - you know me.

To bring it back to opera, consider that Verdi's La Traviata begins at a beautiful party and a party girl luxuriating amidst a rich paramour's baubles and ends with her broke, dying, all her remaining furniture being carted away as she dies in bed, alone but for a nurse who wonders if she'll ever be paid. Substitute Tony's paranoia for Camille's noble self-sacrifice, i.e. her betrayal of her courtesan code by turning noble, and the way Tony sacrifices his empire because of some dumb refusal to kill kids, and then you see it all so plain... Tony is a whore.

To bring it back to opera, consider that Verdi's La Traviata begins at a beautiful party and a party girl luxuriating amidst a rich paramour's baubles and ends with her broke, dying, all her remaining furniture being carted away as she dies in bed, alone but for a nurse who wonders if she'll ever be paid. Substitute Tony's paranoia for Camille's noble self-sacrifice, i.e. her betrayal of her courtesan code by turning noble, and the way Tony sacrifices his empire because of some dumb refusal to kill kids, and then you see it all so plain... Tony is a whore.

To bring it back to opera, consider that Verdi's La Traviata begins at a beautiful party and a party girl luxuriating amidst a rich paramour's baubles and ends with her broke, dying, all her remaining furniture being carted away as she dies in bed, alone but for a nurse who wonders if she'll ever be paid. Substitute Tony's paranoia for Camille's noble self-sacrifice, i.e. her betrayal of her courtesan code by turning noble, and the way Tony sacrifices his empire because of some dumb refusal to kill kids, and then you see it all so plain... Tony is a whore.

To bring it back to opera, consider that Verdi's La Traviata begins at a beautiful party and a party girl luxuriating amidst a rich paramour's baubles and ends with her broke, dying, all her remaining furniture being carted away as she dies in bed, alone but for a nurse who wonders if she'll ever be paid. Substitute Tony's paranoia for Camille's noble self-sacrifice, i.e. her betrayal of her courtesan code by turning noble, and the way Tony sacrifices his empire because of some dumb refusal to kill kids, and then you see it all so plain... Tony is a whore.  |

| Fade to Black, from sun to setting sun image to dark marble death |

Looking back at it now on an anamorphic DVD (after decades of watching it religiously on pan and scan VHS), Scarface looks badly blocked: sets seem to end a few feet from the side edges of the screen and the backdrops often look like freestanding drywall in the midst of slow waterlogged-curling. We start the film sensing this will be a big budget panorama: Cuban refugee stock footage, crowded sweaty scenes under-highway encampments, dishwashing, stabbing, twilight phone booths, the wild Colombian chainsaw set piece, but then the gradual tightening noose of opportunity boils it all down to that La Traviata garrett. As Tony "makes his own moves" there are only a few places to be, and fewer actors stick around as the scenes tighten up in a forward Apollonian arc that begins to wither into fecund limpness: real Miami sunshine devolving to that car dealer backdrop of a sunset, its edges just visible enough on either side of the action to seem meta-textually accidental; hot disco lady dancer montages devolve into some dorky dancing 'El Gordo.' More and more mirrors dilute Tony's vibrancy, as if the vast empire of Scarface merchandise was already draining his snarl of tragic meaning. The architecture eventually turns to gold trim and black marble (a symbol of death like the 'X' markings in the 1932 version) that Gina finally enters like a ghostly echo with her flimsy negligee open and gun like the fish-eyed demoness at the climax of Suspiria. I'll go even further on a limb and say that Suspiria borrows quite a bit in color and nightmare logic pacing from De Palma's big break-out Carrie which came out the year before (1976 -though Carrie was still in theaters, and drive-ins by then, as it had become such a cultural landmark even parents were going to see it).

|

|

But this crazy "Fuck me Tony" scene with Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio and her nightmare black halo and temple of Dionysus sacrificial dress, is where De Palma truly comes to life: mixing that queasy, death-saturated Argento color scheme and slowed-down time (which he mastered with the nightmare pace of the prom queen stair climb in Carrie) with the queasy sense of post-modern sexual displacement emblematic of his idol Hitchcock (i.e., Tony can't realize he's in danger until it's 'on TV'). Not until this final bloody incestuous kiss-off does De Palma find the pitch black death rattle wide-eyed in the face of horror wit that Hecht and Hawks understood better than any others before or since --though for them the preparation for facing death took courage, the actual death itself was a bit of a joke, whereas with De Palma death comes before there's much time to fix a game face, but the actual process of dying stays as felt and faced as in the grimmest of Italian horror films.

Despite all his problems, Tony lives on today, twenty years later, as a kind of living demi-god - his image is as ubiquitous within hood cosmology as Tupac, Jesus, and Che Guevara. But as a character he has aged less well than the the emulators might think. If there's something heroic about his "say 'ell to my leedle fren!" last stand, it's tempered by his blindness to his monitors, his letting his security team get slaughtered, his own impulse killings of Manny and Alberto the Shadow. Mired in cocaine and confusion, he pulls the plug on his existence by letting his coked-up ego and repressed love of kids and guilt over his mama get the best of him (sooner or later, the apron string hydra wins out). His final shoot-out can be read academically as a zero point tantrum of grief and self-absorption. He doesn't know how to handle success, but blazing shoot-outs? Why not - if it comes to him, delivered like a pizza so he doesn't have to try and cook. He's comfortable when he has nothing to lose, but having everything is too much responsibility, especially if his mama won't take any of it.

To get back to the "Italian thing" - one aspect we admire about these mama-free men is how true they stick to their working class roots. Scarface was--the original version--modeled very clearly on Al Capone, so naturally the Untouchables' version Al Capone doesn't let wealth compel him to hide his working class roots. Note the pic below where he's getting shaved by his old barber in a beautiful palatial space under twisted dark manly flooring. This is wealth spent by the man, to realize his aesthetic, not to placate some rich wife's drive for respectability. No flowers, white tiles and dinner parties with all the best snobs. This is instead the nouveau riche bachelor in full flower, wherein the dark sleek look of the Corleone compound, the Italian aesthetic, free of WASP petit-bourgeois wife redecorating, is allowed to flower in its own dark orchid fashion, and it is beautiful, because darkness is beautiful and because today's man gets only one room, his 'man cave' in which to express his taste.

Despite all his problems, Tony lives on today, twenty years later, as a kind of living demi-god - his image is as ubiquitous within hood cosmology as Tupac, Jesus, and Che Guevara. But as a character he has aged less well than the the emulators might think. If there's something heroic about his "say 'ell to my leedle fren!" last stand, it's tempered by his blindness to his monitors, his letting his security team get slaughtered, his own impulse killings of Manny and Alberto the Shadow. Mired in cocaine and confusion, he pulls the plug on his existence by letting his coked-up ego and repressed love of kids and guilt over his mama get the best of him (sooner or later, the apron string hydra wins out). His final shoot-out can be read academically as a zero point tantrum of grief and self-absorption. He doesn't know how to handle success, but blazing shoot-outs? Why not - if it comes to him, delivered like a pizza so he doesn't have to try and cook. He's comfortable when he has nothing to lose, but having everything is too much responsibility, especially if his mama won't take any of it.

To get back to the "Italian thing" - one aspect we admire about these mama-free men is how true they stick to their working class roots. Scarface was--the original version--modeled very clearly on Al Capone, so naturally the Untouchables' version Al Capone doesn't let wealth compel him to hide his working class roots. Note the pic below where he's getting shaved by his old barber in a beautiful palatial space under twisted dark manly flooring. This is wealth spent by the man, to realize his aesthetic, not to placate some rich wife's drive for respectability. No flowers, white tiles and dinner parties with all the best snobs. This is instead the nouveau riche bachelor in full flower, wherein the dark sleek look of the Corleone compound, the Italian aesthetic, free of WASP petit-bourgeois wife redecorating, is allowed to flower in its own dark orchid fashion, and it is beautiful, because darkness is beautiful and because today's man gets only one room, his 'man cave' in which to express his taste.

The only real separation between Italian-American gangster films and Italian-Italian horror perhaps is that death is where the gangster film stops, but horror keeps going. And the brutal circumstances of that trip, the violence of going out, is everything. If you look at non-Italian American horror of the same approximate time, once it appears, death doesn't dawdle. Even most slasher films, the American ones, like Halloween, are really about the stalking and POV camera: when death comes it's almost a relief, since as I pointed out in "A Clockwork Darkness", we now know where the killer is, so there's no more worrying from where and when he will strike, how the person will die or if they will escape. They're dead, so they're safe. For the slasher era suspense-sufferer, no onscreen death can match the dread of not knowing when it will strike. But Argento's murders, De Palma's or Scorsese's or Coppola's first two Godfathers, are the exceptions: the moment of the first bullet, stab, or slash doesn't necessarily end the escape chances of survival, or mean a close to the episode. Death throes might go on for a full reel of near escapes, feeble cries for help, and forlorn looks up at the uncaring sky or (as in Fulci's Don't Torture the Duckling) busy highway, pleading for someone to stop...

And architecture plays another part in prolonging the sense of helplessness. In the apartment building where the first murder goes down in Suspiria, the multiple reflective frosted windows, the bizarre wallpaper, strange vertical angles, unholy lighting, and the howling, strange music and create a sense of complete alienation, an inescapable interior 'Hotel Overlook'-style space (though far less recognizable), we feel we recognize from our own nightmares. We're never sure what is a mirror and what a window; the smoked glass of the bathroom shower stall seems to look right out on the hallway elevator!

De Palma is more rooted in the concrete at least in Scarface, and his vision less baroque, more enthralled by the surface, the mirrors reflecting Tony in ever increasing distortion. De Palma has a natural tendency to use crane shots to create a mood of unease. In the climax, it is Tony himself who is the Mater Suspiriorum, or rather Mater Testiculorum Fide and the Bolivian hit squad is Jessica Harper sneaking in with her sewing scissors.

And architecture plays another part in prolonging the sense of helplessness. In the apartment building where the first murder goes down in Suspiria, the multiple reflective frosted windows, the bizarre wallpaper, strange vertical angles, unholy lighting, and the howling, strange music and create a sense of complete alienation, an inescapable interior 'Hotel Overlook'-style space (though far less recognizable), we feel we recognize from our own nightmares. We're never sure what is a mirror and what a window; the smoked glass of the bathroom shower stall seems to look right out on the hallway elevator!

De Palma is more rooted in the concrete at least in Scarface, and his vision less baroque, more enthralled by the surface, the mirrors reflecting Tony in ever increasing distortion. De Palma has a natural tendency to use crane shots to create a mood of unease. In the climax, it is Tony himself who is the Mater Suspiriorum, or rather Mater Testiculorum Fide and the Bolivian hit squad is Jessica Harper sneaking in with her sewing scissors.

In the above quotes at the top of this article I wanted to exhume the roots of the Italian artistry as the constant need to escape from mama (or even kill her symbolically, as in Suspiria). In the end of Scarface, Tony realizes even a macho endeavor like criminal empire management can turn him matronly ("Got tits," he drunkenly laments to Manny, visualizing his future as another complacent Lopez, "need a bra"). I say unto thee, blessed is the filmmaker who can recognize his own mom-haunted apron-string slashing anger as art and not feel the need to apologize to both women and the social order in general for his venting. As long as he's conscious of it. And both Argento and De Palma revere strong women, but fear them as well. They are conscious of the animas' warped ferocity and respectful of its power. A strong woman can make a man feel outgunned at every step, emasculated (since nothing he can do--even killing--will ever measure up to the raw violence of giving birth) but if he can stare death square in the face and say hello to his little friend --this is his balls. And balls alone can deliver us into the sad twisting architecture of the last breath, the byzantine nightmare realm where reality and dreams switch place, and life disappears like those fading scraps of a dream after you just woke up.

Mom would pull you back from that void. She's afraid you'll fall. If you heed her, you no longer have your balls, just your word, and the words is: be good, call more often, and take out the trash. Being a safe distance from the void may please her, but bores the rest of us stiff. God bless the director who says mama, back off-a me, and then dives right over the ledge with his camera

He who chooses hell over heaven, death over life, he is alone truly free of those apron string jelly fish stingers. He looks at the modern reverence for life, health, the family, and winces. He knows these gym rats and granola moms are all just scaling heights to nowhere, preserving their mortal husk on entomology's display board both in vain and vanity (or that old excuse, 'for the kids'). We men are from birth trained to apologize for our own measly drives, our desire for younger girls rather than the husks our own age; we apologize even our desire for death, and so we follow some vague plan of being 'good' or even 'true' -- yoking ourselves ever further beneath the plow to compensate for our inexcusable appendage. Missing the brass ring circle of light on the swim out of the merry-go-round abyss, we may well wind up permanently trapped in Lucifer's pool filter. All we can do when that happens is throw some of our magic seeds out onto the grass over our heads and hope it's enough to leave some kind of weed in our name that will survive the mower. All we had in this world was balls and words, but mama's world can find no use for either. Our writing is still ours, at least, unless-a someone pays us for the rights. Either way, our balls are yours, Cook's Tours! Take them around that womb globe. Sow their seed like Set sowed Osiris's chopped-up body, or else get stuffed, into the palatial tree coffin, the polluted womb. Marry well and often and love your chil--no, don't do either, just run! Run before she gets here she .../// Vito! Where are you going now, you silly boy!

See Also:

Two hearts stab as one: Brian De Palma + Dario Argento = split/subject psychic twins of the reptile dysfunction

.jpg)

.jpg)