Tick-Tockality: (i.e. tick-tock momentum) The sense of dread created in a good horror film through use of prolonged real time (or slower) narrative pacing (where five minutes of real time crosscut between three characters would take closer to fifteen). Much use is made of the magic hour and the dread it conjures of oncoming night, and the big areas of deep darkness in which anything might be hiding. First seen in the films of Val Lewton (in their 'spooky nighttime walk sequences, always their centerpiece highlight), and later in John Carpenter's Halloween, and The Fog and Don Coscarelli's Phantasm. The desired effect is a sense of inescapable existential dread of what's coming and/or unseen, imbuing even innocuous details with uncanny unease.

Part of the success of this strategy may stem our familiarity from childhood with historical dramas, wherein whole decades fly by between busy but static tableaux of eventful key moments (coming-out parties wherein the news of war first breaks out, and Scarlett and Rhett first dance, and she's wearing red even though her fiddle-dee husband just died, etc. in Gone with the Wind. We become used to the idea that we wouldn't see something if it wasn't foreshadowing and advancing to the story. With this 'training' of our ability to 'read' a film, slower movement within a single 'ordinary' scene --where nothing special seems to be happening (such as Rhett's daughter's riding her pony around on the track while her parents watch) fill us with dread i.e. there's only one reason they'd linger on a close-up of the bitchy star as she walks down the dressing room stairs in wobbly heels, step-after-step, in a 30s show biz musical with her nicer, younger understudy waiting in the wings. Tick-tock momentum subverts our familiarity with this tactic and wrings maximum juicy suspense from it: just keep showing foreshadowing details like the ankle, and keep going from there, each slow step, building the suspense with a progression of possible foreshadowing so that even innocuous minor details are imbued with uncanniness and anxiety about the coming of the night, helping us appreciate what may be our last moment, like the sweet beauty a good cinematographer can get at magic hour making the sky blaze pumpkin orange, making the coming night all the more dreadful for the lack of light.Maybe you need to have been an impressionable, easily-spooked kid in the latter part of the drive-in's heyday (the 70s). Terrifying commercials for R-rated horror movies at the local drive-in would play during local TV's endless comfortingly goofy old monster movies, making our blood run cold. The drive-in was not to be taken lightly. But when you got to go, you were usually with your parents, seeing something a little more family-ready, but we could still feels giddy apprehension as we all parked and watched the setting sun, eager for the darkness to come but scared of it anyway. And then the trailers. You might be seeing some big blockbuster with the folks, but the trailers were free to make you freeze up with fear.

Such a movie was Phantasm I don't remember what movie we were saying but I vividly remember seeing the trailer while the darkening sky still had some orange. had seen a lot of scary trailers (When a Stranger Calls' was my nadir) but nothing this utterly weird. That steel ball in that sterile grey bathroom-style mausoleum, the long-haired little burnout kid, the mysterious man in black with the long arms. It seemed terrible yet terrifying. No one element was itself scary, but it lingered in the mind of every kid who saw it

No one would ever make a movie like Halloween now because so little actually happens until the last 25 minutes. Carpenter and co-screenwriter Debra Hill spend a lot of time establishing what girl is picking up what guy to come over to whomever's house once it's free free of parents (with Hill taking the time to provide accurate, real life girl dialogue) at which time, checking in on the phone with each other--but it's still scary just from music and camera POV location; that's the tick-tock momentum. Imagine how much less scary it would be if they showed other random people getting knocked off, stressing the blood and body count over character... then you'd have crap like Halloween 2.

I mention this because prior to directing and writing Phantasm (1979), Don Coscarelli was shooting kid movies, like Kenny and Co, in which he showed a real knack for connecting with 70s-style sci-fi fan reprobates -- the ones like me-- who would have punched you in the face rather than admit they cried at Benji (1974).

Phantasm's genesis began when Don wanted to adapt Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes but then Disney snagged the rights. So Coscarelli crafted his own dark fairytale about a tall strange visitor who comes to town and steals souls, setting it in a mortuary instead of a carnival and making the central relationship not between various members of a small town, but the relation between a recently orphaned kid, his cool older brother, and their cool friend, Reggie, an ice cream truck driver (any kid's ideal friend for his older brother). We kids generally hated to see kids in movies, but scrappy kids who could throw down in a fight were OK. And we could relate that the real nightmare for this kid is being abandoned as his older brother--his sole caregiver--is immanently going to drive off and leave him all alone in their suburban 70s shag carpet home.

Rated R as Phantasm may be, this is clearly a kid's nightmare: macabre as Burton or Roald Dahl, but with more genuine menace, guns, cool cars, and garage lab gore. It's Over the Edge meets It Came from Outer Space. As boys learning about it from our own older brothers and babysitters, the film became the ultimate myth-a film about us but denied us until we were old enough, or until it showed up on TV, its fangs plucked for prime time. This time the kid isn't a sap; he's good with cars and knows how to make a gun from a shotgun shell, a thumb tack, and a hammer. He rides a dirtbike and has long wavy hair. He tapes a hunting knife to his ankle, drinks beer, and is smart enough to use a lighter to keep a coffin lid propped up just high enough see out of without drawing attention (and cool enough to have a lighter in the first place and have it be no big deal) and he knows how to drive, and his brother throws him the keys, and gives him a shotgun and doesn't tell him to keep it unloaded and practice gun safety like a mom would, but that he should shoot it only if he means to kill, with no warning shots "are you listening to me? Warning shots are for bullshit").

Rated R as Phantasm may be, this is clearly a kid's nightmare: macabre as Burton or Roald Dahl, but with more genuine menace, guns, cool cars, and garage lab gore. It's Over the Edge meets It Came from Outer Space. As boys learning about it from our own older brothers and babysitters, the film became the ultimate myth-a film about us but denied us until we were old enough, or until it showed up on TV, its fangs plucked for prime time. This time the kid isn't a sap; he's good with cars and knows how to make a gun from a shotgun shell, a thumb tack, and a hammer. He rides a dirtbike and has long wavy hair. He tapes a hunting knife to his ankle, drinks beer, and is smart enough to use a lighter to keep a coffin lid propped up just high enough see out of without drawing attention (and cool enough to have a lighter in the first place and have it be no big deal) and he knows how to drive, and his brother throws him the keys, and gives him a shotgun and doesn't tell him to keep it unloaded and practice gun safety like a mom would, but that he should shoot it only if he means to kill, with no warning shots "are you listening to me? Warning shots are for bullshit").

Story-wise, the weird secrets of the other dimension and dead soul enslavement make a nice contrast to these cool moments, providing a fine metaphor for not just where parents go when they die but where they work, the void they disappear into for most of the week, before they come back beaten and bowed low. The big fear is where older brothers go when they're off doing cool adult shit and you're not allowed, following him anyway, giving us a POV window into the adult world we barely understand (Mike's binoculars see all sorts of things he shouldn't). Just as we dread the dark secrets our older brother is up to, yet crave to be let in on them, we fear having to get a job out there in that mysterious void one day, a day coming slow but inexorable towards us, like we're on an escalator and afraid of being sucked under its jagged teeth.

In the Spielbergian make-over of children's horror films in the 80s, kids lost that edge of looming responsibility, quick-thinking and readiness for violence, but in the 70s we knew we weren't safe, parents were far more lax, and so we felt exposed to the dangers around us. They wouldn't protect us, but they wouldn't bother us either. The freedom made us sharp. All the joys of life were outdoors, ideally at night. We didn't have cell phones. When we had to sleep we clutched toy guns like rosaries. Today's parents think any kid with a gun is going to cause a Columbine, that anything too scary will give them nightmares. So fucking what if they do?! They should have nightmares. If they have any brains, they know enough to be scared. Shit is scary out there and you're too little to do much about it except run. When you're a young kid, most women are stronger than you in a fight. We can't do much except cringe, run, or suffer. Spooky movies just remind us to stay on our guard, to not let the sameness of modern life trick us into slackening our grip on that plastic trigger. Let the adults take the facade of death, the mausoleums and funerals, at face value, as kids we saw deeper, we noticed the little details didn't add up, and we knew nothing was ever as secure as the funeral director's measured tones tried to make it. We could feel the real terror of pain and anxiety of 'anything can happen,' feel it in the skin of our knees and the electricity fooding our lower spine.

|

| Ruscha gets it |

I mention this because prior to directing and writing Phantasm (1979), Don Coscarelli was shooting kid movies, like Kenny and Co, in which he showed a real knack for connecting with 70s-style sci-fi fan reprobates -- the ones like me-- who would have punched you in the face rather than admit they cried at Benji (1974).

Phantasm's genesis began when Don wanted to adapt Bradbury's Something Wicked This Way Comes but then Disney snagged the rights. So Coscarelli crafted his own dark fairytale about a tall strange visitor who comes to town and steals souls, setting it in a mortuary instead of a carnival and making the central relationship not between various members of a small town, but the relation between a recently orphaned kid, his cool older brother, and their cool friend, Reggie, an ice cream truck driver (any kid's ideal friend for his older brother). We kids generally hated to see kids in movies, but scrappy kids who could throw down in a fight were OK. And we could relate that the real nightmare for this kid is being abandoned as his older brother--his sole caregiver--is immanently going to drive off and leave him all alone in their suburban 70s shag carpet home.

Rated R as Phantasm may be, this is clearly a kid's nightmare: macabre as Burton or Roald Dahl, but with more genuine menace, guns, cool cars, and garage lab gore. It's Over the Edge meets It Came from Outer Space. As boys learning about it from our own older brothers and babysitters, the film became the ultimate myth-a film about us but denied us until we were old enough, or until it showed up on TV, its fangs plucked for prime time. This time the kid isn't a sap; he's good with cars and knows how to make a gun from a shotgun shell, a thumb tack, and a hammer. He rides a dirtbike and has long wavy hair. He tapes a hunting knife to his ankle, drinks beer, and is smart enough to use a lighter to keep a coffin lid propped up just high enough see out of without drawing attention (and cool enough to have a lighter in the first place and have it be no big deal) and he knows how to drive, and his brother throws him the keys, and gives him a shotgun and doesn't tell him to keep it unloaded and practice gun safety like a mom would, but that he should shoot it only if he means to kill, with no warning shots "are you listening to me? Warning shots are for bullshit").

Rated R as Phantasm may be, this is clearly a kid's nightmare: macabre as Burton or Roald Dahl, but with more genuine menace, guns, cool cars, and garage lab gore. It's Over the Edge meets It Came from Outer Space. As boys learning about it from our own older brothers and babysitters, the film became the ultimate myth-a film about us but denied us until we were old enough, or until it showed up on TV, its fangs plucked for prime time. This time the kid isn't a sap; he's good with cars and knows how to make a gun from a shotgun shell, a thumb tack, and a hammer. He rides a dirtbike and has long wavy hair. He tapes a hunting knife to his ankle, drinks beer, and is smart enough to use a lighter to keep a coffin lid propped up just high enough see out of without drawing attention (and cool enough to have a lighter in the first place and have it be no big deal) and he knows how to drive, and his brother throws him the keys, and gives him a shotgun and doesn't tell him to keep it unloaded and practice gun safety like a mom would, but that he should shoot it only if he means to kill, with no warning shots "are you listening to me? Warning shots are for bullshit"). And the car his brother drives is a badass Plymoth Barracuda. Dude but that is a seriously bossed-out car (as we used to say - boss is probably equal to "lit" or "clutch" today)

Plus, what a neighborhood. No one seems to live anywhere, but there's an old lady fortune teller neighbor, and great little bits, like when Reggie drops by with his guitar for a quick porch jam. It always seems to be either late night or late evening in that tick-tockable early fall kind of way, where the darkness seems to rush up on you way too soon and when it does, everything is jet black darkness and very quiet. Aside from the memorably but perhaps overused score it's a film quiet enough you can hear the wind rustle in the graveyard trees. We hear about a sheriff, but we never see him, nor anyone other than the brothers, Reggie, and the girl with the star on her cheek, her blind grandmother psychic, and a girl who runs an antique store (the only thing apparently open in the entire town, it's comforting colored lights sticking out in the dark like a vulnerable oasis.

Story-wise, the weird secrets of the other dimension and dead soul enslavement make a nice contrast to these cool moments, providing a fine metaphor for not just where parents go when they die but where they work, the void they disappear into for most of the week, before they come back beaten and bowed low. The big fear is where older brothers go when they're off doing cool adult shit and you're not allowed, following him anyway, giving us a POV window into the adult world we barely understand (Mike's binoculars see all sorts of things he shouldn't). Just as we dread the dark secrets our older brother is up to, yet crave to be let in on them, we fear having to get a job out there in that mysterious void one day, a day coming slow but inexorable towards us, like we're on an escalator and afraid of being sucked under its jagged teeth.

In the Spielbergian make-over of children's horror films in the 80s, kids lost that edge of looming responsibility, quick-thinking and readiness for violence, but in the 70s we knew we weren't safe, parents were far more lax, and so we felt exposed to the dangers around us. They wouldn't protect us, but they wouldn't bother us either. The freedom made us sharp. All the joys of life were outdoors, ideally at night. We didn't have cell phones. When we had to sleep we clutched toy guns like rosaries. Today's parents think any kid with a gun is going to cause a Columbine, that anything too scary will give them nightmares. So fucking what if they do?! They should have nightmares. If they have any brains, they know enough to be scared. Shit is scary out there and you're too little to do much about it except run. When you're a young kid, most women are stronger than you in a fight. We can't do much except cringe, run, or suffer. Spooky movies just remind us to stay on our guard, to not let the sameness of modern life trick us into slackening our grip on that plastic trigger. Let the adults take the facade of death, the mausoleums and funerals, at face value, as kids we saw deeper, we noticed the little details didn't add up, and we knew nothing was ever as secure as the funeral director's measured tones tried to make it. We could feel the real terror of pain and anxiety of 'anything can happen,' feel it in the skin of our knees and the electricity fooding our lower spine.

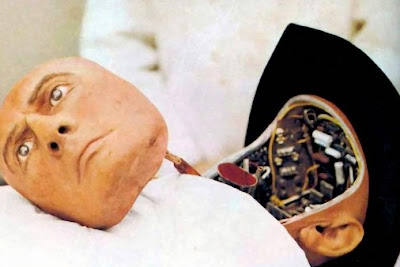

In its fuzzy horror glory, Coscarelli's Phantasm's mythos is totally unified even its freeform reversals and misdirections. Once can connect it to Lovecraft as well more recent 'nonfiction' writers like David Icke, Nigel Kerner, who theorize that after death our newly separated souls might be intercepted by a demonic force before we reach the white light, and then used as fuel for UFOs, or ground up for experiments and recycling. Our souls could be picked over like the bloodless cattle mutilations. The main Phantasm bad guy (Angus Scrimm) known only as The Tall Man turns souls into weapons (the spiked, silver balls) and stores the crushed down bodies into kegs for easy shipping home to his dimension through a tuning fork gateway --the use of sound vibrations to transfer between dimensions is also legitimate weird theory, 'acoustic levitation' which ascribes the building of pyramids by using sound vibration to convert huge stones to weightless floating states.

A great example of a real case near-death experience (NDE) that fits this bill pretty well can be found in Nick Redfern's Final Events. "(Paul) Garratt said that he was confronted by a never-ending, light blue, sandy landscape that was dominated by a writhing mass of an untold number of naked human beings, screaming in what sounded like torturous agony" the sky was filled with pulsing flying saucer crafts, he watched them stop above the people

A great example of a real case near-death experience (NDE) that fits this bill pretty well can be found in Nick Redfern's Final Events. "(Paul) Garratt said that he was confronted by a never-ending, light blue, sandy landscape that was dominated by a writhing mass of an untold number of naked human beings, screaming in what sounded like torturous agony" the sky was filled with pulsing flying saucer crafts, he watched them stop above the people

"then bathed each and every one of them in a green, sickly glow.... small balls of light seemed to fly from the bodies of the people... which were then sucked up into the flying saucers."

"At this point, an eerie and deafening silence overcame the huge mass of people, who duly rose to their feet as one and collectively stumbled and shuffled in hundreds of thousands across the barren landscape--like in a George Romero zombie film--towards a large black-hole that now materialized in the distance." (99)I don't know if Coscarelli has read up on NDEs or not; perhaps his vision originated in a zone of his unconscious where the dark (but subjectively interpreted), coupled to some direct film references, which to his credit Coscarelli doesn't deign to hide: the tall man's evil minions look like jawas (Star Wars was only three years old); the way darkness laps at the edges of the screen and the tick-tock score echo Halloween (the year before); an old lady fortune teller works one of those hand-in-the-box Dune fear-control tests on Mike. What Coscarelli does originate is bringing an edge of brotherly surrealism, removing any sense of inequality between waking and dreaming life: Mike's sudden wake-ups from nightmares don't carry the feeling of a cheap scare for no reason like they do in American Werewolf in London or Cat People (1982), for example. With Coscarelli, like Lovecraft, Lynch, or Bunuel, dreams are just as valid as the waking life, maybe even more so, He's not just sticking references in there to try and cover all his bases and provide weird trailer moments, Coscarelli's mythos is straight from the land of mythos, of fairy tale Jungian crypto-archetypal unconsciousness, a cross between a Hardy Boys book and a dime bag of dirt weed.

COMETH THE SEQUELS

If you go all the way through the first four films of Phantasm seriess, you wiull have to dig the rapid aging of the cast, because the four main principles from the first film -- the kid, A. Michael Baldwin (as Mike, though he's played as older by a different actor in part 2 (James Le Gros), Bill Thornbury as his older brother Jody, Reggie Bannister, and as the sinister tall man, Angus Scrimm -- all stick around for the subsequent installments, which were released over a 20 year period but may be set only months apart. It's a shock to see what is supposed to be merely a few days or hours later within the overarching narrative take such a massive toll on their faces, hair, and body shapes. Myriad worry lines drain Reggie's Jeremy Piven-style charimsa until all that remains is a sad guy trying to get laid in a world full of yellow blood vomit hell cops. He looks beaten but still fixing up sheds to look like seduction zones, moseying up to strange women in ghost towns, and wearily quipping after killing foes of various sizes. Action movie qui[s grew stale by the late 90s, but Reggie didn't get that memo. But if you let it be, such things are part of the series' charms, the Phantasm series never gets any memo.

THE TICK-TOCK INITIATION

Maybe all children have to learn to be masochists just to survive, so small and helpless are they, and part of that may come from our ancient use of male initiation ceremonies to demarcate the line between manhood and boyziness: girls don't need initiation since nature has menstruation to traumatize them, forever; but male initiatory tribal ceremonies understood the psychological need for such trauma in boys as well. It only survives today in the form of, alas, fraternity or military hazing, but those are rites initiated by choice; a boy in a tribal society has no choice--it's inescapable, and that dread's allowed to build and build. We then lost that sense of inescapable dread/initiation until the 70s when it was gratified by our dread of the gore in our first R-rated movie. We who trembled at the coming drive-in night were unique in that respect: R-rated films didn't even exist when our parents were kids, and then video arrived during our teenage years, making it suddenly possible for our younger siblings to rent Clockwork Orange and Dawn of the Dead and watch them over breakfast with our moms. Any fear of R-rated gore never has any time to generate.

But in the 70s, just knowing hard stuff was only out there, at theaters that we couldn't get into, launched an electirc gravitic dread in our spines, like I get now only when looking straight down while leaning over a tall building without a handrail.

The most terrifying commercial ever for me in that regard was Torso (1973). The raspy male voice that used to hiss "Rated R...." after shocking 2-3 second snippets of scenes---like this sexy girl pleading and crawling through the mud in her nightgown while a masked killer advances on her with a hacksaw-- burned into my soul, and I'd get that sickly sexual twisting feeling, the type I only get now from looking over a dangerous ledge or plunging down a log flume.

But with VHS, that giddy terror gave way (for me at least) into depression from watching too many bloody horror movies instead of being outside playing, and from a kind of negative misogynistic osmosis, as well as a crushing disappointment that no amount of pan and scan TV room horror could ever compete with what we had imagined. And yet we had already seen too much, that was the problem - there was just sooo much of this stuff that it became dreadful. We lost our faith in our fellow man and the feeling of being safe in our suburban houses at night. It had really begun, for me, probably with renting A Clockwork Orange (the first movie I ever got mom to rent) and seeing the rapes and violent videos Alex sees, all raw and shocking yet dull and flat, they seemed like, real, as if a fake movie within a fictional film somehow created a double negative, and so these films played real. (the way they do with the snuff films found in the film, Vacancy [4])

So yeah, I attribute the rise in overprotective parental hysteria and nanny state fascism almost entirely to the arrival of video and the sudden availability of every movie we ever heard of, movies we knew we'd never see on TV, or if we did, all the 'bad' stuff edited out. We gained overexposure to imaginary danger at the expense of exposure to actual physical kind; in the process we also lost the rite of initiation. If the minute after hearing about some gruesome scene in a movie you can watch it on your phone in class, well, you don't have time to get scared, so there's nothing to have to use courage to overcome. It's just a lot of fake blood and acting. There's no initiatory fear and catharsis. You might be building a tolerance for violent images, but that's not going to help with the initiation rite your soul hungers for and your mind and body fear. There's no ceremony to mark your courage, i.e. your first R-rated movie. The first one I saw? Outland (1981), at 14. Alan's very cool, muscle car driving older brother bought us tickets. We heard guys exploded from exposure to space sans suits, and that's where the dread came from. It was something to boast of. The older brother regarded my trepidation without snickering, admiring my feint of courage, telling me "you'll be fine." (And of course I was, but the fear of gore made the experience of an otherwise ho-hum sci-fi movie transformative).

Now of course anything even approaching some sort of hazing as a passage to becoming a man is considered a crime, but even the shockmeisters knew that engendering the fear of what was coming was more important than the thing itself. Generating fear helps us realize there was never nothing there to fear in the first place. Facing it, our older cooler friends feel obligated to be nice to us, to let us into the cool world. (see Dazed and Confused.) Running away from the fear stifles you and earns contempt. Seeing Mike and Jody roaring down the road in their '71 'Cuda (below) brings that back. This was a time when life was dangerous, and most importantly, so were we. (See also my analysis of the best movie about being a kid in that era, Over the Edge).

Awash in desolate suburban blight, dark, twisting woods, empty plains, fire-damaged barns, cobwebs trailing down from street signs, Phantasm leaves us with the feeling one has crossed somewhere back from banal day reality into unreal nightmare. These landscapes do exist, even more so now. I saw this desolation most in western Oregon. Every storefront along the road closed and boarded up and not a soul for miles and miles, yet you feel your car is being followed some tall shadow you try to tell yourself is only a tree in the dark of your rearview. Your tank's been on 'E' for an hour and when you see that white light in the distance you know it's a 24-hour Exxon station dropped from the sky by God's Jesus's own flying saucer. Every fellow traveler you meet smiles at you, for they too have survived the swallowed darkness of the empty expanses of highway and the feeling the world has ended and together you are grateful in a profound deep way only spooked lost travelers riding on empty through abandoned countryside know, or people leaving a very scary movie as one quivering mass edging towards their cars.

To get back to that frame of mind, where the setting sun strikes you with giddy drive-in terror and you long for the woodsman Exxon deliverer, first you have to surrender your 80s guns and your 90s disaffection and your 00s sincerity. Return to the time horror movies created far more dread with a single modulating synthesizer than any overthought orchestra, when R-rated movie storytellers worked each other into frenzies of fear, describing events from films they'd seen or heard about, lingering over the traumatic scenes and embellishing on what they heard as needed for petrifying effect. (2) This is what Phantasm is all about, the fractured but impelling rantings of an imaginative child's mind as he hears the scraping of the branches on the window and tries to sleep; it comes to us as a half-dream hybrid myth, already re-spun by a telephone game's worth of spooky child imagination, it's fiction for the boy seeking initiation into guns, beer, muscle car engines, cigaettes and more beer--the lore of the cool American older brother. It's fiction, yet it still feels truer than anything contemporary adulthood has to offer.

NOTES:

1. The 'blanks' --such as the fate of the captured girls (Reggie just says he found them and released them but we never see it) were probably a result of drastic cuts made by Don himself. According to the trivia notes on imdb: "This film's original running time was more than three hours, but writer/ director Don Coscarelli decided that that was far too long for it to hold people's attention and made numerous cuts to the film. Some of the unused footage was located in the late 1990s and became the framework for Phantasm IV: Oblivion. The rest of the footage is believed to be lost. " -Now that'a a damn shame, even if the unused footage is brilliantly mixed into IV and does save it from the edge of crappiness.

2. I'm still finding movies I remember hearing about from other kids, like Five Million Years to Earth, and Phenomena, movies I was sure were made up by their teller, or wildly exaggerated,

4. See: 2004: Collateral Torture (Bright Lights After Dark)

But in the 70s, just knowing hard stuff was only out there, at theaters that we couldn't get into, launched an electirc gravitic dread in our spines, like I get now only when looking straight down while leaning over a tall building without a handrail.

|

| The ad that scorched my 6 year-old mind |

But with VHS, that giddy terror gave way (for me at least) into depression from watching too many bloody horror movies instead of being outside playing, and from a kind of negative misogynistic osmosis, as well as a crushing disappointment that no amount of pan and scan TV room horror could ever compete with what we had imagined. And yet we had already seen too much, that was the problem - there was just sooo much of this stuff that it became dreadful. We lost our faith in our fellow man and the feeling of being safe in our suburban houses at night. It had really begun, for me, probably with renting A Clockwork Orange (the first movie I ever got mom to rent) and seeing the rapes and violent videos Alex sees, all raw and shocking yet dull and flat, they seemed like, real, as if a fake movie within a fictional film somehow created a double negative, and so these films played real. (the way they do with the snuff films found in the film, Vacancy [4])

So yeah, I attribute the rise in overprotective parental hysteria and nanny state fascism almost entirely to the arrival of video and the sudden availability of every movie we ever heard of, movies we knew we'd never see on TV, or if we did, all the 'bad' stuff edited out. We gained overexposure to imaginary danger at the expense of exposure to actual physical kind; in the process we also lost the rite of initiation. If the minute after hearing about some gruesome scene in a movie you can watch it on your phone in class, well, you don't have time to get scared, so there's nothing to have to use courage to overcome. It's just a lot of fake blood and acting. There's no initiatory fear and catharsis. You might be building a tolerance for violent images, but that's not going to help with the initiation rite your soul hungers for and your mind and body fear. There's no ceremony to mark your courage, i.e. your first R-rated movie. The first one I saw? Outland (1981), at 14. Alan's very cool, muscle car driving older brother bought us tickets. We heard guys exploded from exposure to space sans suits, and that's where the dread came from. It was something to boast of. The older brother regarded my trepidation without snickering, admiring my feint of courage, telling me "you'll be fine." (And of course I was, but the fear of gore made the experience of an otherwise ho-hum sci-fi movie transformative).

Now of course anything even approaching some sort of hazing as a passage to becoming a man is considered a crime, but even the shockmeisters knew that engendering the fear of what was coming was more important than the thing itself. Generating fear helps us realize there was never nothing there to fear in the first place. Facing it, our older cooler friends feel obligated to be nice to us, to let us into the cool world. (see Dazed and Confused.) Running away from the fear stifles you and earns contempt. Seeing Mike and Jody roaring down the road in their '71 'Cuda (below) brings that back. This was a time when life was dangerous, and most importantly, so were we. (See also my analysis of the best movie about being a kid in that era, Over the Edge).

|

| This. This you can trust. |

To get back to that frame of mind, where the setting sun strikes you with giddy drive-in terror and you long for the woodsman Exxon deliverer, first you have to surrender your 80s guns and your 90s disaffection and your 00s sincerity. Return to the time horror movies created far more dread with a single modulating synthesizer than any overthought orchestra, when R-rated movie storytellers worked each other into frenzies of fear, describing events from films they'd seen or heard about, lingering over the traumatic scenes and embellishing on what they heard as needed for petrifying effect. (2) This is what Phantasm is all about, the fractured but impelling rantings of an imaginative child's mind as he hears the scraping of the branches on the window and tries to sleep; it comes to us as a half-dream hybrid myth, already re-spun by a telephone game's worth of spooky child imagination, it's fiction for the boy seeking initiation into guns, beer, muscle car engines, cigaettes and more beer--the lore of the cool American older brother. It's fiction, yet it still feels truer than anything contemporary adulthood has to offer.

---------

NOTES:

1. The 'blanks' --such as the fate of the captured girls (Reggie just says he found them and released them but we never see it) were probably a result of drastic cuts made by Don himself. According to the trivia notes on imdb: "This film's original running time was more than three hours, but writer/ director Don Coscarelli decided that that was far too long for it to hold people's attention and made numerous cuts to the film. Some of the unused footage was located in the late 1990s and became the framework for Phantasm IV: Oblivion. The rest of the footage is believed to be lost. " -Now that'a a damn shame, even if the unused footage is brilliantly mixed into IV and does save it from the edge of crappiness.

2. I'm still finding movies I remember hearing about from other kids, like Five Million Years to Earth, and Phenomena, movies I was sure were made up by their teller, or wildly exaggerated,

4. See: 2004: Collateral Torture (Bright Lights After Dark)

.jpg)