Is hysteria at the root of comedy in the same way sex is at the root of hysteria? Or has fear of being a bad father replaced sexual repression as the self-exposing terror at the heart of the modern persona? Has the removal of spanking as an acceptable from of behavioral correction in our current era of overprotective rod-sparing in fact altered parenting and childhood to such an extent that the neurosis at the heart of repression is no longer a sublimated sadomasochistic incestuous taboo but fear of being branded a bad father? Without the threat of spanking to anchor his authority, the father becomes the child, living in mortal terror of being accused of spanking or, at a more acceptable Hollywood plot level, being branded a bad dad and thus spanked by the ex-wife and her lawyer with the rod of alimony.

Watch A DANGEROUS METHOD and LIAR LIAR in the same day and the whole crazy charade comes clear: Cronenberg's 2011 film chronicles a passionate lapse of ethics on the part of Jung (Michael Fassbender) with his sexually unhinged masochist patient, Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley). As Freud, Viggo Mortenson smokes cigars and feigns shock at his mentee's weakness but is he maybe jealous? Even though with her hysterical symptoms including a frightening distending of her jaw, Knightley's Spielrein is still super hot. As she gets 'cured,' her madness abates and she is "allowed" to go to medical school and become a psychoanalyst herself, but hot mess-wise it's like she dries back into the scenery.

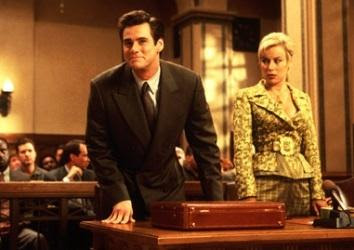

Jim Carrey's 1997 film by contrast follows two days in the life of a high-powered lawyer who specializes in unscrupulous larger-than-life lying. He's never around for his son's birthdays or ball games or whatever and he's divorced but when Jim does finally show up he's a riot, apparently. The son loves him, but is getting mighty disillusioned about his father's constant empty promises. When he's present, of course, Carrey's emotionally arrested spastic antics make him the ultimate in 'fun' dads, but it's these same qualities that code him sexually arrested. He's a fun dad but useless as an actual parent or presumably as a lover. His is the opposite of the suffocatingly masculine sexual presence of Sabina's unseen father and his apparently frequent corporal punishments. One is far too rigid a suffocating authority figure, the other far too genial and mostly absent. When Carrey's son's birthday wish comes true it means his dad can't tell a lie for 24 hours, but unfortunately within that frame he has to win a big important divorce case that's a handy mirror to his own life. When it all goes to shit he's forced to beg his son try and undo the 'curse' via another birthday ritual.

But of course Jim's inability to lie is wherein lives the comedy. Forced to be bluntly truthful in his statements to the court, Carrey gets to twist and spazz impressively in a textbook example of Jung's autonomous complex, wherein the subject is emotionally arrested, unable to cope with adult reality, a split subject at war with itself. As such a subject:

"... the significance of archetypal defenses is relatively greater. When the ego is not developed, the damage is more catastrophic. The psychic defenses are more primitive and archaic, such as splitting and projective identification. The inner world is full of rage and violent aggression, which is split off or dissociated into fantasies or autonomous archetypal forms, which threaten to turn against the self and others. There is not an adequate ego to deal with the rage or with the split off forms which are invested with aggressive, destructive energies. (Singer, Kimbles, p. 160)

The differentiation of Carrey's post and pre-epiphany persona (for these comedies always end with the dad realizing what's 'important' in life - i.e. the family) hinges merely on the sublimation "for good" of the autonomous complex Jung describes. Carrey's performance of "the claw" (above), a hand he cannot control, keeps his son amused (and is thus good) while his spastic herky jerky in the courtroom endangers the sanctity of the legal profession (and thus is bad). By ultimately leading Carrey to a self-realization (he quits his job to spend more time at home with his son) the autonomous complex 'wins' and forces Carrey to relocate to a place where said complex has its approved outlet -- forever amusing the son in the seclusion of the home (with 'the claw'). Carrey remains unable to actually eliminate the complex, merely finds its correct outlet, just as Sabina eventually finds hers in her own doctoral practice. Once Sabine steps out of her ascribed domestic sphere and enters psychiatry school she's cured of her spastic distended jaw hysterics while Carrey steps into the domestic sphere to find a place for his. In other words, in each case the symptom must be contained and harnessed into a place opposite the one ascribed by gender norms.

As it's a love story we root for the forbidden passion of Sabina and Jung in METHOD, their affair is an autonomous complex that cures each of its victims of all sorts of positive traits, such as doctor-patient bonds and professional ethics-- and leaves them wiser and complex-free. In the end, Jung and Sabina keep their jobs: Sabina marries someone else and Jung pops out more kids still with his long-suffering wife, all while Freud looks on, askance. Lucky for them, neither Jung's nor Sabina's issues involves the trials of parenting. Jung avoids his kids at least in the film (and lives in a time when such remote parenting was accepted) and yet childhood parental relations are at the core of his secret affair, as in the whipping and spanking of Sabina during their trysts.

So while Carrey finds an outlet for his undeveloped ego's hysteric split in amusing his son with an autonomous hand 'claw,' which only pretend-threatens corporal punishment (triggering jouissance in the child), Sabina and Jung find an outlet for their own jouissance by not sparing the rod within themselves. Jung's claw (the whip) becomes a surrogate for Sabina's father's spanking hand, while Jung himself gets to escape the crushing guilt over his own real-time absentee fathering through this re-enactment of a role as Sabina's corporal pater. Just as his whip hand acts as surrogate to the hand of her father on Sabina's ass, if you'll forgive the expression, Carrey's claw wraps around his own neck. Perhaps when Carrey's son grows up his girlfriend (or boyfriend) in college will deliver her (or his) own version of 'the claw' on him, by his own kinky request, and the cycle will be complete.

Back in the day I dismissed Carrey, along with 'idiot savant' film stars like Adam Sandler and Jerry Lewis, as lowbrow buffoons strictly for the kids and the French. But armed by DANGEROUS METHOD, Carrey's schtick glows with archetypal dementia that explains my overall reticence, my fear of squirming on the gender-based guilt hook. Now that I've made that leap, these spastic males I used to hate can join the pantheon modern apocalypse dads I wrote of awhile back for Bright Lights (See: Dads of Great Adventure) wherein I suggested that the hook of modern disaster movies is no longer fear of dying but "having it be your fault if your children die, are wounded or abducted while you have them for the weekend." It's a very real fear dads of today have, far worse than they used to, but in a way it's a cop-out: you avoid imagining your own death or taking responsibility for your own happiness by just imagining being 'in trouble' with the wife when she finds out.

Conquering fear is of course a huge part of the sadomasochistic complex, but such a complex precludes any by-proxy nonsense such as what the anxious dad obsesses over, imagining his child being spanked by some stranger in a white van, i.e. living a by-proxy terror for his son. The "this is going to hurt you more than it hurts me" speech that used to prefigure a spanking becomes literal, as the father spanks himself at the mere thought of anyone ever so much as touching the behind of his child, unless that someone is a qualified physician or his own mother but that's none of his business, thank god.

Or worse, the child missing, going missing on his watch, having it be his fault. Better a thousand deaths than that.

|

| Hold yourselves together, Jimbo |

It's still a noose, this domestic trap, just a looser one; eventually the outright avoidance comedic dad returns. Unable to maintain his fragile ego against TV's injunction, his sense of self and purpose leaking out of him like a sputtering balloon, he flees into the realm of the infantile, which is where we usually find him when the film begins. Having received his karmic lesson after the climax, he goes racing back to share his 'changed man' status with his son, who is imminently departing (with mom) for a new life with a bland and simple 'perfect' soon-to-be stepdad. This new guy usually has a good supportive job and is 'there' for the son in ways the actual guilt-ridden dad is not (a step-dad isn't expected to be perfect, thus he's free from guilt and can actually be present).

No one in LIAR sees a shrink but they should, in order to see that it is the unbearable pressure of being a perfect TV dad that drives the 'real' dad away; the 'new' bland dad is just the castrated version, the pod person, who has trimmed away the excess jouissance that has no place inside the bland confines of the ascribed nuclear family. He's a cautionary example (to moms with their TV high standards) of getting what you wish for. The new dad is useless as a father because of his perfection. What the real dad does have, what he can bring the stepdad can't, is, eventually, hopefully, a way to incorporate some of the wildness that drove him from the family in the first place. The dad must bring the wild back into the family, learn to take charge, even punish and be an authoritarian figure if need be, to not need to be the 'friend' all the time, not need to be loved, not let himself by paralyzed by fear of being judged according to the Perfect Man Rule Book, but to bring in his boots of eccentricity rather than leaving them at the door (and if the wife says they're too muddy, for example, she or the son can bloody well clean them). He needs to 'take 'er easy' as a dad and not hover over the boy; if he's terrified that at any moment some fathering challenge may erupt and expose his lack, he must hide it, must fake it til he makes it. Because if he's going to let his fear show, he's going to do more harm than good.

What the dad fears is/isn't there underneath his shaky, undifferentiated persona isn't there under anyone else's either -- it's just that the bland stepdad never had the illusion it was. The Carrey style dad feels he's the only one who feels that way, so a solution, like a carrot on a stick, dangles ever near... the problem with that stick is, whatever spastic pleas for adoration consume him at the moment invariably make him late for whatever's next on his agenda; prior commitments are forgotten in the rapture of the moment. A differentiated persona internalizes the split so instead of one hand doing something (say strangling himself) against the rest of the body's will, the subject can go ahead and act like a lunatic with his whole body, but keep 'one eye on the time.'

Unfortunately in METHOD we're not allowed to stop at the moment of true blissful union between Sabina and Jung the way we stop with father-son reunion LIAR. Instead there's Jung's bitter mishandling of rumors about him (which it turns out were spread by Jung's wife), his insistence the passion he and Sabina have found must be internalized, cut-off due to peer pressure. Eventually Sabina finds a way to split the hysteric masochist off into her other sexual encounters, while Jung finds the moxy to challenge Freud and follow his own drummer into the realms of the mystic - even terrorizing Freud with displays of telepathy. What Carrey is so afraid of in LIAR--that even if he parents with all his heart he may still be found wanting-- is supposed to happen. All dads must inevitably be found wanting to be true dads, otherwise the child just suffocates from cardboard perfection. It's something Freud realizes with a heavy heart while on a ship to America with Jung, who brings him a dream that predicts Freud's passing into history. It's something to be proud of but with the glory of 'passing into history' comes the realization of no longer being cutting edge. Freud will become part of the same closed-minded establishment that used to boo him out of conferences. Freud accepts it with the understanding grace of a true psychoanalyst, a true father. After all, to do less would void his own theories.

It's necessary, this final rejection by the edge, this merging into 'establishment' and empty symbol - it's the final lesson. No one can stop time from stepping on Freud's or Jim Carrey's faces until all that's left is a graying portrait on the wall. The difference is Freud knows it, and can thus can play his part and then get on with his smoking. The Carreys of our world refuse to accept this, so never get to the level where they can finally accept the truth, which is that the only good father, in the end, is a bad father, i.e. a good father pretends to be a bad one when a bad one is needed. Children need a father who can say no and be stern in some things, can frighten them with his manly authority if needed, and have fun and be merry if not. The wise and differentiated father knows when it's time for the son to be disillusioned and rebel, when it's time to be symbolically buried, and to let his son move on, to not whine or cajole if his sone eventually comes home only at Christmas (or if married, every other Christmas); all fathers say, awkwardly, "here's your mother" after 30 seconds of phone call small talk. Only the good fathers don't feel bad about it.

Bad "authoritarian" dads mistake their role for their actual self, and wreck their children's lives by micromanaging them long into adulthood--they are never the 'fun dads' who let their kids party in the basement. A bad "fun" dad, by contrast, refuses to take the role of authoritarian, never notices when he's being intrusive, overstaying his appearance at all his son's basement parties. A good dad stays upstairs, lost in Handel, but will snap into it if, for example, there's a fire or he's in a good mood and comes down for five minutes to grumble and grin then roll his eyes and say 'keep it down to a roar' before trundling upstairs). Otherwise fuck you, man, he's listening to Handel. Having raised a great son he cuts him loose like a painting he's spent decades working on and now must sell to a private owner. Freud may cling to his idea that the 'repressed sub'-conscious is the whole unconscious and rant against the new kids who've found endless levels of basement below that one, but perhaps it is just an act. An artist may cry and stamp his foot but he knows that just drives up the value when it's time to sell the painting. A good dad is always down to let the prodigal wander, and to take comfort in his sixth cigar of the day as he fades into irrelevance in his paintings' lives. And that's why there can be no self realization without tobacco, Anna. Or death neither.